The Amateur

A small window into the life of a man who feels truly, truly larger than life.

“An absolutely brilliant and soulful read.” Adédoyin’s take on a Vistanium story. Be the first to know when the next the next thing drops.

One could begin with the smell of rotting refuse from the three garbage trucks in front of the abandoned sports centre at Rowe Park. Or start with the gibberish scribbled on the road partition from Sabo-Yaba all through Herbert Macaulay Way. But the old man, stationed at the gate of the old library adjacent to Rowe Park, barely registers these.

Instead, he walks silently down the road, a fixture in his Adidas tracksuit. He leaps over the concrete road partition, passes the garbage trucks, and jogs down the narrow road to Alagomeji. Sometimes he stops along the road, shuffles his feet and throws a flurry of blows into the air, each jab followed by hard gasps of his breathing—“ahh-argh-hegh!”—and then, reaching the junction, he turns and walks down the main road.

At this time of the evening, groups of area boys exchange loud banter at different corners of the road. A few stop and hail the old man, their hands in the air, “Up Coach!” He grins, responding with a hearty, “Ahhh! Well done!”

About an hour later, the old man jogs his way back down the dirt path toward the old library, his tracksuit drenched in sweat, dripping from his brows down his chin. He lives alone in the security room apartment in front of the National Library and has remained there since he knocked out Àlàbá and hung his gloves in 1990.

In the small room, a shelf holds a stack of books, old photos and record albums he rarely plays. On one side, three untuned guitars lean against the wall, alongside boxing cassettes, a piano and a trumpet that gather dust and, on the other, wall nails support a makeshift clothesline, where tracksuits and security uniforms hang to dry. Above his boxing gear is an old photograph of him cradling a trophy. Just outside the room are two chairs and a table, where he sits all day until someone calls, “Mr Okafor!” or a car honks at the gate, or when, in a rare moment, he reveals to a curious visitor what it is like to be a boxer in Nigeria.

In the late 1940s, the Okafors, both young Cambridge University graduates, worked for the Lagos colonial government. The husband was a military officer at Marina, while his wife was a department manager at Kingsway Stores, the most exclusive retail chain in colonial British West Africa. It was located on Broad Street, near Lagos Marina.

The couple often took an annual break from work every December and would travel to the husband’s hometown in Issele-Uku, Benin province, with their children for the holidays. One year, something strange happened: before they returned home to Lagos, two of their twelve children fell sick and died after a few months.

This strange cycle continued every year – first, the twin boys, then the twin girls followed – and by 1948, eleven children had died.

On their last trip to the village, their only surviving child, Michael Ayodele Okafor, was also on the brink of death; a fever burned his body from the inside, and his tongue began to peel.

Michael’s mother had had enough. “I will not marry you again!” she cried, “Your people are killing my children. Take me back home to Abeokuta! I can't stay here anymore!”

With only one son left, she fought to keep him alive. She collected different kinds of medicine and fed them to the boy. When he barely responded to treatment, she sought Ifa’s guidance. She covered him in an iron pot with punctured holes, crying to Ṣàngó, Ògún, Ṣọ̀pọ̀ná, and all the gods her ancestors worshipped.

Three years passed, and Michael Okafor grew into a healthy teenager. They’d moved back to Lagos, and he’d returned to Standard Four in the neighbourhood school. His mother remained overprotective. She’d say to every kid in the neighbourhood, “Abeg, na your friend? Don’t knock his head! Na me and you go die with am.”

When a teacher beat him, she’d show up in school, wrapper tightened, and say, “Una don kill eleven, you wan kill this one again?!”

“Na so she do so tey dey pack me one side, they no dey teach me book again,” M. Okafor recounted, “I became scared of my mother; she made me feel weak.”

When he was fourteen, his teenage yearning for independence turned into something else.

First, he’d skip school, over the fence, and off, lurking around with boys in the neighbourhood. He'd often return home late to a worried mother.

“I became a rascal boy,” M. Okafor said.

His rebellious streak continued until one day, colonial officers spotted him as he roamed the streets during school hours. When they brought him to his mother, the neighbours advised, “Let them take him away. When he gets there, the white men will be able to control him.”

If you’re new here, someone shared this with you or shared it where you’ll see it. I hope you’d like Vistanium. Trust their judgement: subscribe.

Isheri Welfare Home, Ojodu Berger, was a correctional centre for juvenile delinquents to re-socialise, re-educate and re-integrate the boys into society. They could opt for formal education, technical work, music, or sport and were free after obtaining a certificate for whatever they learned. It’s where M. Okafor spent the next eight years of his life.

There, he wasn’t the only boy beyond parental control; the centre was home to bigger boys with worse vices, and his rebellion was no match.

While waiting in line to draw water from a well one afternoon, a hefty boy suddenly pushed him to the back. He tried to fight, but the bigger boy crushed him. Defeated, he retreated to the dorm room and sobbed uncontrollably. He despised life at the centre just as he had at home, but there, he felt trapped.

When the day came for him to choose how he’d spend his time, he chose music, carpentry and boxing. In music, he found escape; through the piano, trumpet and guitar. Boxing gave him control, direction, and one place to channel his anger and frustration: a punching bag. He was hooked.

It felt good to hit something. But after sparring a few times with boys in his category, he suffered yet another beating that left him questioning his decision. The dangers of boxing stared him in the face, and doubts crept in. He wasn’t sure he could continue down the path or if he had what it took to continue fighting. The uncertainty lingered, but he was determined to push forward, to prove something to himself.

The Isheri coach would say: “Listen up boys, I know you’re all here for different reasons, but I want you to know that this sport can take you places you never thought possible. You put in the work, and you could be standing on that Olympic podium. And it’s not just about the winning, it’s about the person you become through this process. You’ll develop the discipline and resilience to push through pain. And when you go pro, you’ll earn a lot of Nigerian pounds, more recognition and power.”

He knew that the path to becoming a pro boxer was difficult, he needed to train hard to develop his strength, and repeatedly win at the amateur level.

“Ahh-argh-hegh!”He’d train at every chance he got. He couldn’t sleep without training or fighting.

***

The welfare home often brought professional boxers to train the boys and occasionally took them to the Shell Building at the National Stadium, Surulere. They’d mix and train with amateur boxers who came from different boxing clubs in Lagos, from Idumota to Ikorodu, Isale Eko, and Costain. Hogan “Kid” Bassey, the first Nigerian to become a world boxing champion, had returned home to coach amateurs. Along with other coaches, he’d watch the boys spar in the boxing arena, analyse their strengths and weaknesses and show them how to improve.

About a year after Nigeria’s independence, M. Okafor made the team for what would be his first local tournament. The Isheri boys headed to the Shell Building to participate in the annual inter-club open championship. “We be like stick wey no dey move to woman,” M. Okafor recalled, “Nothing dey wey go make us happy; we always dey ready to attack.”

He was competing in the welterweight category. He stood across another boy, Fidelis Onye Som, and dropped him twice in the first round for the mandatory count. Fidelis stood up and threw a flurry of punches at M. Okafor, putting him down for a count in the second round. He got up and mounted pressure, outpointing Fidelis over three rounds. Okafor would later discover that the opponent he’d defeated had been the Lagos welterweight champion, and his name has since stuck like glue. Fidelis.

***

M. Okafor felt like he’d finally found something he was good at, and so his ambition grew. He would go pro, then become a world champion, just like Hogan “Kid” Bassey or Dick Tiger.

After completing his time at the welfare centre in 1962, he returned home to his mother, who eagerly introduced him to a young girl. “I was 23 when they married for me, and I never knew anything about lovemaking or marriage; my mother would force me and tell me how to relate with my wife.”

It was time to meet her grandchildren and make up for the children she’d lost. “We (my wife and I) quarrelled many times, and I’d leave her at home for days, but my mother would always come to settle the matter. If it weren’t for her, I wouldn’t have stayed with the woman,” he said.

Amateur boxers didn’t earn money from the sport until they turned professional. He needed some form of stability.

With the carpentry skills he picked up at the welfare home, he got a daily wage job with the Nigerian Railway Corporation in Lagos in 1963. He worked with other carpenters to construct and repair wooden railway structures and was paid 10 shillings after the day’s work. He earned a cumulative income of 200 shillings monthly, which was equivalent to 10 Nigerian pounds. After a year of working at the Nigerian Railways, his wife had their first son. At 24 years old, he was now a family man, which meant he had more mouths to feed, but he couldn't abandon his boxing aspirations.

He’d look at his arms, fists and chest in the mirror and was sure he could one day become a world champion; he just needed to remain determined. The Nigerian Railway Corporation had a boxing club, and after a few months of working, he was scouted for the team. After work hours, he’d train and compete in local tournaments.

He was good and quickly became the captain of his club, but he still was no match for the Costain Club boys like Karimu Young and Nojim Maiyegun, who qualified for the 1964 Olympics. Maiyegun won a bronze medal in the light middleweight category that year. It was every amateur's dream to make it to the Olympics, but M. Okafor didn’t make it past the inter-club trial at Shell Club in 1964.

***

He continued to train relentlessly at the Railway Club until May 30, 1967.

At 2 a.m. that Tuesday in Enugu, over 500 km from where M. Okafor trained, the military governor of Eastern Nigeria, Emeka Odumegu Ojukwu, delivered a speech. Surrounded by diplomats and journalists, he declared:

“...Now, therefore, I, Lieutenant-Colonel Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, Military Governor of Eastern Nigeria, by the authority, and pursuant to the principles recited above, do hereby solemnly proclaim that the territory and region known as and called Eastern Nigeria together with her continental shelf and territorial waters shall henceforth be an independent sovereign state of the name and title of “The Republic of Biafra…”

The Nigerian government, led by General Yakubu Gowon, declared a police action to arrest the secession, and war broke out a few weeks after. It didn't matter that he'd lived in Lagos for most of his life or that he didn’t feel Igbo; his last name was Okafor, and he wasn’t safe.

“I had to run away,” he said, “I was forced to run to my father’s hometown in the Midwest, the same place eleven of my siblings had met a mysterious fate.

“My wife na from Sapele, and her papa no want make she follow me go. We drag this thing so tey, the father say no, ‘War is coming, let my daughter return home to me. If my pikin go die, make she die for my face.’

“Na so I carry my own pikin go home, make everybody hold their pikin.”

With his little boy’s life in his hands, he packed a small bag and fled.

The Nigerian Railways Corporation had suspended services on several routes; no train could move from Lagos to Benin, and he didn’t own a car. He walked a few miles and stood by the roadside to flag down passing vehicles, hitchhiking through Benin, Agbor, and Umunede until they reached Issele-Uku.

Issele-Uku was located near Onitsha, where the war raged on. The Midwest didn't join the war, but its people weren't immune to the violence.

Neighbouring villages were under attack with residents being murdered. Issele-Uku remained eerily silent, with everyone laying low, barely leaving their huts except to hide on the farm and hunt for food.

“Our mind was not at rest. We run here, we dodge there. If we hear say dey don come, we go run inside farm and stay there for about one or two days.”

On August 9, 1967, 3,000 Biafran soldiers invaded the Midwest, with plans to advance towards Lagos and Ibadan. They crossed the River Niger bridge into Asaba, through Issele-Uku, and upon reaching Agbor, the Biafrans split, with some battalions taking Warri, Sapele and Ughelli.

“The soldiers passed through our village and tried to force us to support Biafra in the war, but we refused. They jaga jaga everywhere and took three of our girls with them.”

By 1968, the war showed no signs of drawing to a close, and devastating news reached M. Okafor, “I hear news say my wife don die for Warri.”

He felt something he hadn’t felt since he was a teenager, an overwhelming need to escape and break free; from Nigeria, where he wasn’t wanted, or Biafra, where he didn’t feel like he belonged.

“During the war, I couldn’t do boxing; everything don scatter.” The war had left no room for boxing, music or anything that truly mattered to him.

One day, he made a decision: he left his four-year-old with his aged father and crossed the border into Cameroon.“I found my way to Calabar, where I entered a canoe to Bamenda, West Cameroon and then moved to Kumba, Douala, before settling down in Yaoundè, the capital of Cameroon.”

The first opportunity Cameroon gave him was music.“A band poached me when I got to Douala; I could play the trumpet, the guitar and the piano. I played Cameroonian Afrofunk and a fusion of Congolese Soukous and Makossa with the band. We made and sold several records.

“To cool off, we’d drink Majunga palm wine and champagne. We had women who liked our music. We called them Jumba. I had six of them. If you no get Jumba, your music no go sell for Cameroon.

“Ah savwa omo, savwa yé ko tamwir, savwa omo, savwa yé ku turu… (Remember, my love, don't forget, know that you must recall…)" he sang soulfully as he struck the keys on his old piano.

The war ended in 1970, but M. Okafor returned to Nigeria with his band in 1972, stopping to pick up his son, and then continuing to Lagos. In the 1970s, Yaoundé, the capital of Cameroon, suffered from a serious lack of established recording studios, causing the band to migrate to Nigeria for better access. “When I came back, my house at Oyingbo was no longer my own. Na property we dey talk? The thing wey I run leave. Everything don follow the war go,” he recounted.

When he was ready to work in 1973, he was reinstated into his old position at the Nigerian Railways. This time, as a full-time carpenter, receiving ₦28 per month. The head of state, General Yakubu Gowon, introduced the Naira on New Year's Day, 1973, replacing the Nigerian pound at a rate of £1 = ₦2.

He’d been staying at a friend’s apartment, but shortly after resuming work, he was compensated with a house at the Railway quarters for the loss incurred from the war. “That ₦28 was big money. I never spent everything before the months ended. Everybody in my family was eating, and we were living in the Railway compound free, with no house allowance.”

He resumed boxing again, continued to compete in tournaments, and by 1980, now 40 years old, he won a medal for boxer of the year within his club.

When it was time for the 1980 Moscow Olympics, he represented his club in the welterweight category but was dropped at the open championship trial. He was still with the band, but after a while of recording and live performances, they went their separate ways in 1980.

In 1984, his team travelled to Bauchi and competed with boxers from other Railway Clubs from across Nigeria. He won first position in the light middleweight/super welterweight category, bringing the cup to Lagos. He’d become one of the best boxers at the Railway Club, and he was certain he’d make the Olympics this time.

It was three months before the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles; he’d made it through the first trial. He competed with boxers from other clubs in an open championship at the Mobolaji Johnson Sports Centre. This time, he made it to Abatti Barracks for the Champions of Champions trial and was invited to training camp. If he made it through this stage, he’d make the Olympic team.“I fought three times and wasn’t knocked out. They said my opponent won by points. Everything is politics o jare. They’ll see a good boxer, but they’d want their person to go, and they have the final say. It wasn’t just me,” he claimed. “They dropped many of us off at the trial.” Charles Udealor, the heavyweight champion then, also claimed he was dropped out of the 1984 Olympics.

“I tried for the Olympics three times, and since they weren’t picking me, I started to lose faith. You already know those with the coaches; you go just dey wahala yourself.”

Out of all the six boxers who made the Olympics in 1984, only Peter Koyenguachie in the featherweight category made it to the finals, returning to Nigeria with a silver medal. Other boxers, including Charles Nwokolo, light-welterweight; Rowland Omoruyi, welterweight; Christopher Ossai, lightweight and Joe Orewa, bantamweight, were eliminated earlier. Only Jeremiah Okorodudu, middleweight, made it to the quarter-finals, and he lost 1-4 to Joon-Sup Shin of South Korea.

Share. When you share, more people find Vistanium.

He was prepared to stop boxing. He was 44 years old, and boxing hadn’t taken him anywhere. Every great Nigerian boxer he knew left Nigeria before they became something — Hogan “Kid” Bassey, Dick Tiger, Nojim Maiyegun, Bash Ali and others. Rafiu King, he said, had also been at the Isheri Welfare Home before he went pro and left Nigeria to fight in France, Switzerland, Italy, the U.S. and other countries.

He’d wanted to go professional too, but “When climbing a tree, you get to a point where you stop. Oò lè gun orí ewé, tí ọ bá dé òkè, ilẹ̀ náà lo nbọ̀, but, èmi òlè dé òkè yẹn, ìyẹn ló bí mi nínú tí ọkàn mi fi kúrò ní boxing (You can’t stand on the leaves. If you get to the top, you’ll still come down, but no matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t get to that top. That made me so angry that I stopped boxing).”

There was no one left to encourage him. He had lost his dad in 1984 and his mother two years before him. Before his father passed away, he’d ask him, “Kí lo nwá ní ìdí boxing yí gan. You wan die?” pointing out boxers who had suffered head injuries and upended their lives.

Muhammad Ali was diagnosed with the neurodegenerative disorder Parkinson's disease (PD) in 1984, which later contributed to his death in 2016. Nojim Maiyegun, the first Nigerian Olympic medalist, gradually began to suffer blindness after receiving several punches to the head.

“Gbogbo àbúrò mi ti kú, èmi nìkan ló wá kù. Mo bẹ̀rẹ̀ sí ronú, ‘Tí èmi náà bá lọ kú nkọ́? Ìya mi á bínú lọ́run (All my siblings have died. I’m the only one left, and so I started to think, ‘What if I died too?’ My mother would be angry in heaven).”

M. Okafor stopped boxing altogether, but he continued to watch local tournaments. When he stopped, his peers from the Railway Club began to mock him for retreating, calling him a weakling. In 1990, he finally accepted the challenge to fight another boxer called Àlàbá.

But amateur boxers would taunt him everywhere he turned on the street, saying, “Àlàbá go kill you for ring.”

***

M. Okafor's anger and frustration over the mockery and his unfulfilled potential had finally reached a tipping point. “Àlàbá? Pa èmi? (Àlàbá? Kill me?)”

He was going to wound Àlàbá. “They thought I was finished, but that just gave me the courage to train harder.” He started to watch Àlàbá’s fighting cassettes to understand his moves.

It was match day at Rowe Park, and Àlàbá fought his way into M. Okafor’s guard, throwing a staccato of punches at his face —“Tah-tah-tah-tah”— pounding away with near-total freedom, despite the occasional block or slip from Okafor. Àlàbá’s uppercut tore the flesh above Okafor’s right eye; he was stronger than he’d thought. M. Okafor stood up, infuriated. Seconds later, he was all over Àlàbá. He went on his toes, jabbing endlessly until the final bell. Àlàbá was so beaten that he had to be rushed out of the ring for medical attention. He’d incurred a penetrating head injury that caused damage to his brain. He remained bedridden for weeks, and after a while, he developed a staggering gait, stammer and tremble of the hand.

Àlàbá was punch drunk; a cognitive impairment, loss of memory, slurred speech, balance disturbances, and abnormal movements, which occurred most frequently in many older or poorly skilled boxers.

“He started sleeping under the bridge and would come to beg money from me here. Any time I see am, I go dey cry. I still dey beg God to forgive me till today.”

Àlàbá never recovered.

***

M. Okafor made a pact to stop boxing altogether, but his coach, Mensah at the Railway Club urged him to take a coaching course to stay relevant in the field. He could be around the ring, close to the sport, but not in it. He pursued a Grade 2 coaching course from the Sports Commission in 1992, becoming a part-time coaching assistant after retiring from the Nigerian Railway Corporation. The inner turmoil that sent him to the ring remained, and he sought healing elsewhere, in church. He found comfort in singing with the choir.

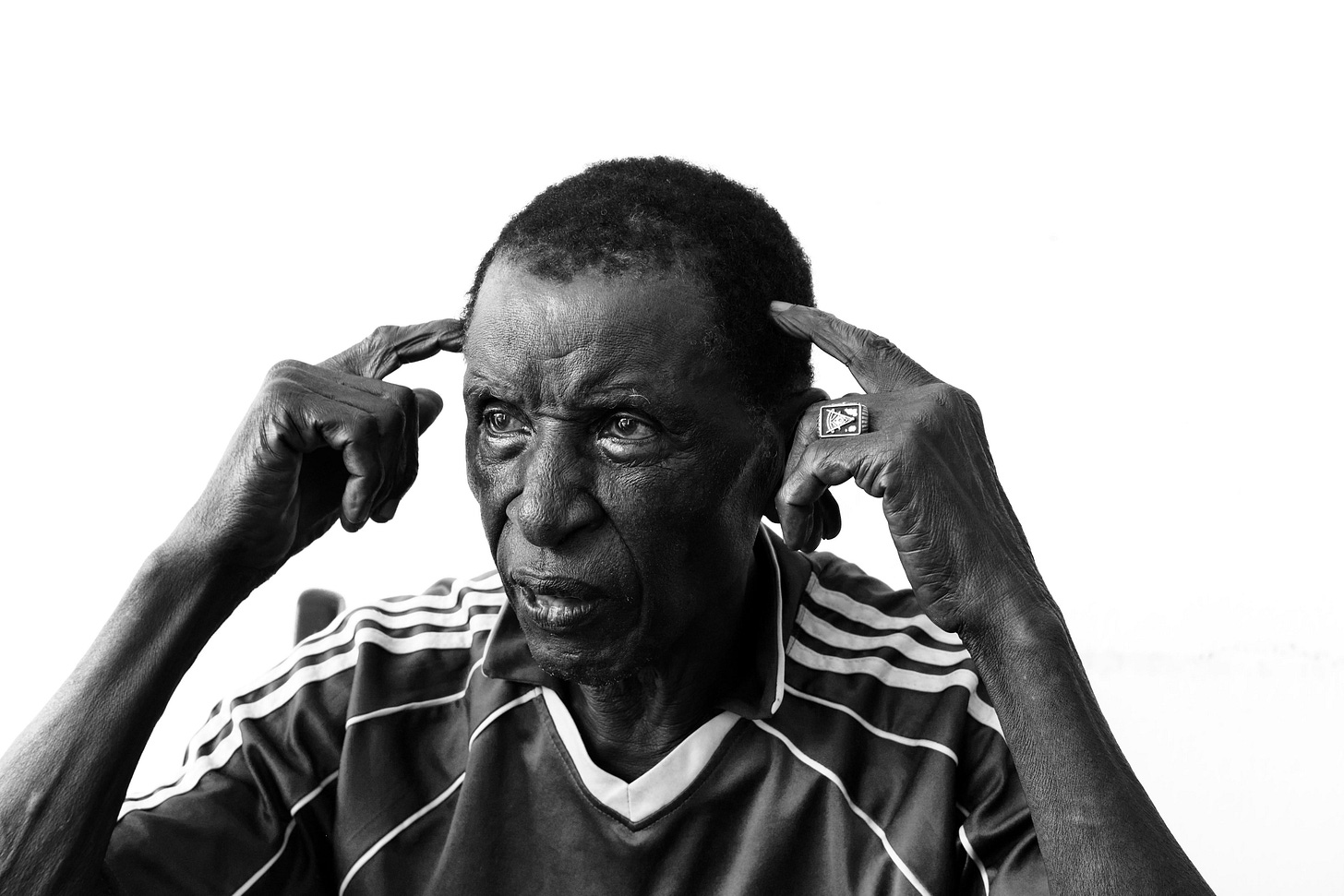

These days, if you go to the National Library in Yaba, you’ll find him sitting close to the gate, agile and healthy for an 84-year-old man. He thinks about his youth a lot. He thinks about Isheri, the Olympics, Cameroon, the Soukous and Makossa, about Àlàbá. “Sometimes,” he said, “I forget things.”

Most of all, he continues to show everyone that, despite his age, he’s not a weakling. Fate continues to test him.

In 2024, a few months after he clocked 84, M. Okafor was at his security post at the library. At around 2 a.m., he heard footsteps and quickly hid behind a door in the hallway. Intruders.

He peered through the window blinds to check if the three intruders were armed. He watched as they entered the admin office and turned over every piece of furniture, looking for something valuable to steal.

As a younger man, he might have been able to take them on. “Ahh-argh-hegh! One-two, lean back; one-two, low dock. But he knew he didn’t stand a chance against three of them.

He stayed hidden for a while, checking to see if they had guns. He took a deep breath, felt for his Freemason ring, then sprung out, dragging his cutlass along the ground.“Kra-kra-kra-kra.” The screeching sound echoed through the hallway, sending the thieves fleeing for the fence and going off with a meagre ₦350 in the drawer.

M. Okafor felt pride, and then he went back into hiding.

If you made it this far, you should probably subscribe.

It Took A Village (and a lot of time) To Bring This Together

It was week one of the 2024 Paris Olympics, and I was researching a story, digging through old newspapers at the National Library, when I overheard an old man expressing his frustrations to the front desk staff with a heated intensity.

He spoke about his past as an Amateur boxer who had competed in many Olympic trials, criticising the government for neglecting the sport and its retired athletes, many of whom had proudly represented Nigeria and won medals. Coincidentally, I was reading a 1986 Nigerian Tribune paper that spotlighted many boxing tournaments in Lagos. I was intrigued. “I’m a journalist,” I said to him. That was the first time I said that to someone with conviction.

I returned the papers and quickly followed him to the security post, impatient and thrilled to listen to his story. That’s where this story begins.

For me, It's one rare encounter to find an 84-year-old boxer randomly. I couldn't wait to ramble about the story idea with my editor, Fu'ad, Nana, and the Vistanium team. They were just as excited as I was about the story.

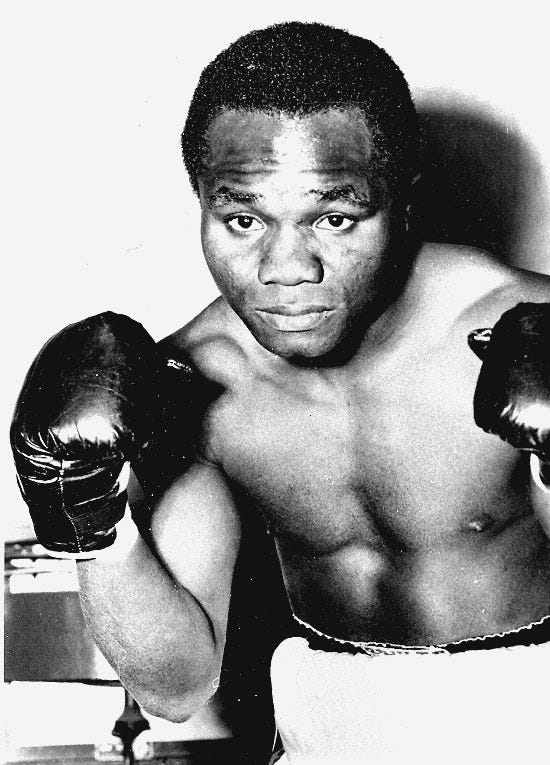

We assembled a team to bring the story to life. Faruq would recreate the 60s boxing nostalgia with his stunning black-and-white photography.

I dialled up my cousin, Harun, and, together with Faruq, we took off to the library the following Sunday. We spent the entire day there, listening and waiting as he tried to remember the little details.

After a while at the library, we headed to Rowe Park for photos. We couldn't get most of the boxing theme shots we wanted because the indoor sports facility had been under renovation for three years. Boxing training now happened in a school park at Alagomeji.

We went to this school the following week and saw how rigorous their training was. Amateur boxers and coaches from clubs all around Lagos had come to train for an upcoming tournament at The Teslim Balogun Stadium in Surulere. I was invited, but upon getting to the stadium the next day, the location was changed to Ikorodu. A coach promised to ring me when there's a new tournament.

After several attempts at drafting a narrative structure, I finally found an arc structure that worked for the story. The editing process was rigorous, with Fu'ad doing the developmental edits, Samson doing copyediting, and Ruka asking the final hard questions.

It took a lot of effort and time to get this published. The only reason this exists for you to read is because of Vistanium’s members. Their membership is what pays for this writing and allows it to exist. If you believe it deserves to exist, then help us make more here.

Oh my goodness! Thank you so much for this.🥹❤️

It tugged on my heart strings in ways that I can't even explain. I guess that's because of the angle that I'm thinking about it from - how you never know where life will take you despite your beginnings (who would have thought that the child of Cambridge grads would live his life in such rough patches? I can't help but wonder in what ways his life would have been different if his parents had never come back to Nigeria,if his siblings would have lived, etc), the long lasting effects that the greed and wickedness of a small group of people can have over the lives of many innocent people (re: The Biafran war - many of the war's architects are gone now but the evil they did will never be completely wiped out), his doggedness and determination in the face of it all (in a way and through the most difficult situations, he kind of lived a full life. I hope his son is alive and well? 🥹). I hope he finds the forgiveness and peace that he yearns for. This piece makes me think about how many people we just pass by everyday not knowing them or what they've been through; I will forever be curious about people and the stories that make them who they are. Thank you so much for this story and for the pictures, too.

Every person is a world of stories. ❤️

And to the people that draw out these tales and weave them into a beautiful tapestry of big emotions and meaning, you are magic.

Thank you, Aisha. You are magic. ✨