Ballot Ballads

A story-led guide on what it means to be young and navigating the Nigerian elections, from 1979 to 2023.

I sat on a bench near an express road in the middle of nowhere, waiting. It’d taken me over two hours to get there from Lagos. I was going to Ibadan to meet a man and had to be there before noon. We’d been discussing over the phone for three months, but I finally insisted we talk in person.

I was enthusiastic about the conversation but also scared to meet an old man I barely knew, alone. I was waiting for my friend, who agreed to come with me.

When my friend finally arrived, I called the man again for directions. One cab trip, and a short walk down a dirt road later, we arrived at our destination. First, it was just a wall, then on the other side, dozens of students were crammed into a long room partitioned into three sections. The roof was patchy, the doorways narrow, and none of the nine windows had burglary-proof or window fittings. Two chalkboards were hung on the wall, and one read “Agricultural Sciences.” This was a school; all of it.

In the middle of the building, grinning and waving his hands, was the man we’d come to see, Kayode, in Ankara shirt and pants. I assumed he’d be many things; a farmer, a this, or that, but the one thing I didn’t expect was that he’d be an active teacher. He put the chemistry textbook he was holding aside to shake our hands and offered us the seats across from him.

***

I struggled to hold a political opinion in the 2023 elections. I was 20, feeling overwhelmed by the media frenzy around the elections while trying to graduate from university. Despite fighting to get my voter’s card and finding my way to the polling booth, I remained undecided. The older folks where I live in Ilorin were convinced the young people supporting the opposition—whether Peter Obi or Atiku Abubakar—were ignorant. It also didn’t help that I knew so little about any of them.

I paced the polling booth nervously and panicked at the thought that my political decision could determine the trajectory of my life over the next decade. So I left the polling unit without voting; the guilt plagued me for months.

It pushed me to a tipping point: I needed to understand what it means to vote in Nigeria, how people choose their leaders, and the factors that contribute to these decisions.

My curiosity led me to old newspapers at the National Library of Nigeria in Yaba, Lagos. I found stories through papers from the 1979 elections, the inception of Nigeria’s presidential democracy. I wanted to see how elections and leadership shape Nigeria.

To ground my knowledge, I spoke to several people: my grandma who remembered nothing but held on to her 1991 NEC-issued voter’s card. An old man – Obe, whose apartment got burned down, alongside his landlord who had supported a different political party in 1983. My friend’s mum, who was an underage voter in 1979. Kayode, I was curious about more than most: he’s voted in every election since 1983, until his recent disillusionment with the political process – with his choices shaped by several underlying factors.

Life in Ṣakí, Oyo State, was simple in the 60s and 70s.

The first day Kayode showed up at school, the Universal Primary Education Programme had already paid for his tuition. Awolowo established this initiative as Premier of the Western Region in 1955.

Every day after school, Kayode would drop his bag and head out to help his parents on their cocoa farm or help his grandfather, a produce buyer. He observed how little they made and swore that one day, he too would become a farmer, but one that actually turned a profit.

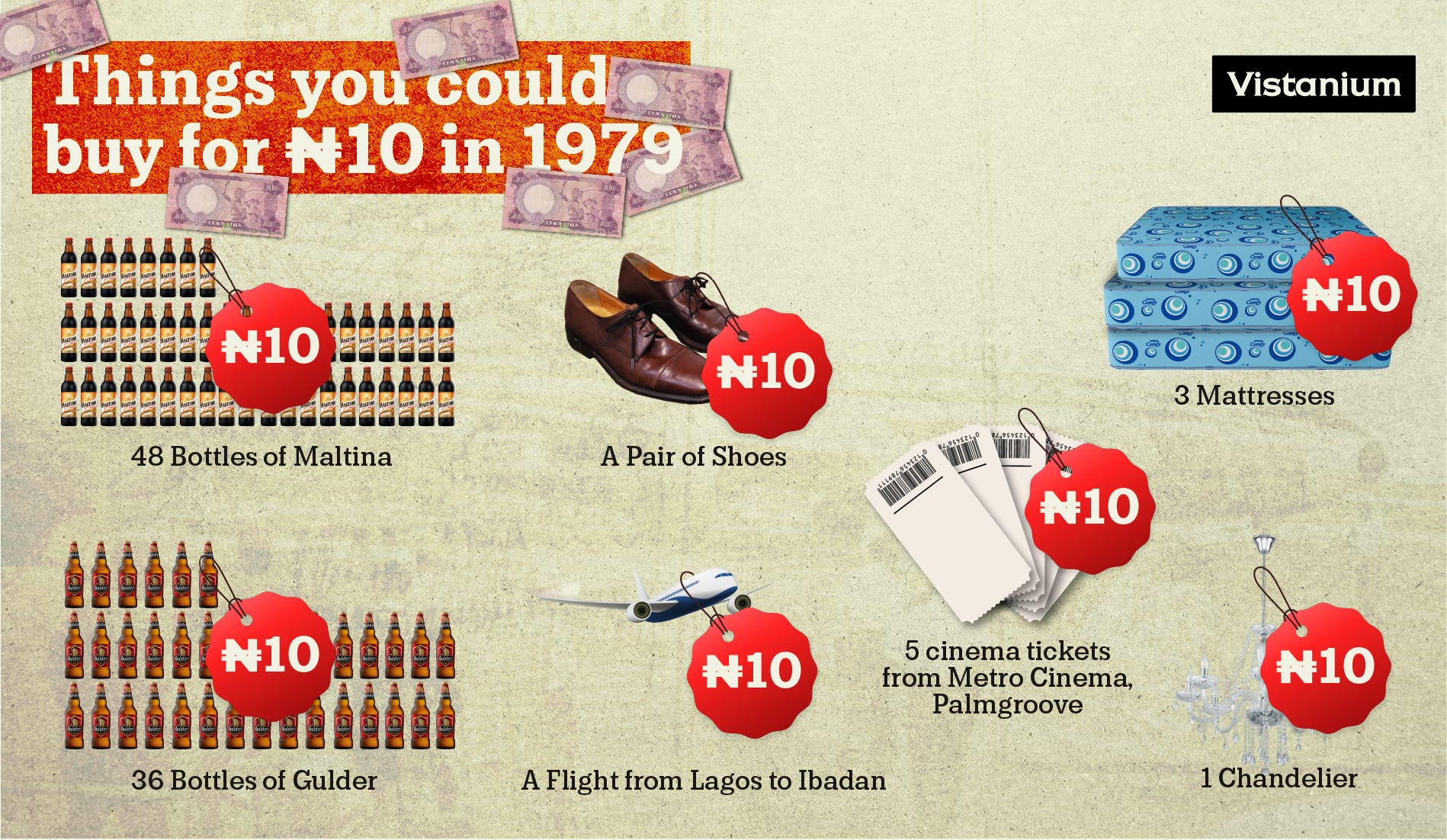

By 1979, just before Kayode completed secondary school, the military government of Olusegun Obasanjo asked every student not to pay school fees – his last school fee was ₦10. That same year, the military returned to the barracks and gave way to democracy. Shehu Shagari, of the National Party of Nigeria (NPN), secured a narrow and controversial victory over Obafemi Awolowo.

Kayode, then only 17, experienced his first Nigerian election. He’d volunteered as an electoral officer at a polling booth in Ṣakí. It felt like being part of a revolution; Nigeria was finally returning to civilian government after 13 years of military rule. This time, the Obasanjo-led military regime decided to go for an American-style democratic system as opposed to the British parliamentary system Nigeria had used throughout the first republic from 1963-1966.

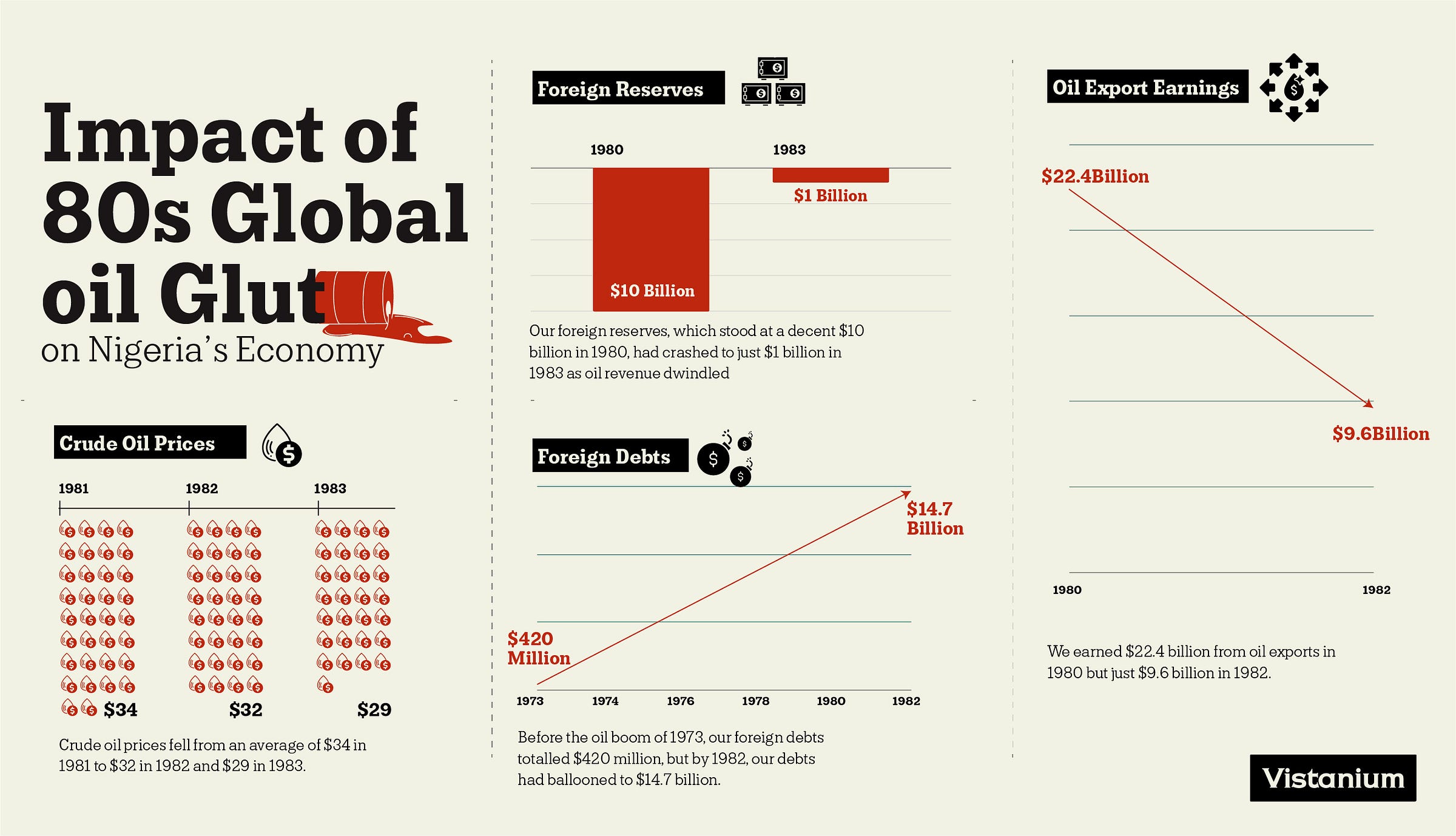

Kayode was eager to see how civilian democracy would play out in Nigeria. Over the next few years, Nigeria started to experience a severe contraction in federal revenue as a result of the global oil glut and the government’s deficit spending. Kayode likened the government’s corrupt tendencies to that of Ali Baba and the forty thieves. The Obasanjo-led regime, he said, had introduced Peugeot 504s for government transport, but when Shagari became president, government officials started to show up in Mercedes.

“They also started importing a lot of rice, which reduced local agricultural production. We used to farm rice at Ilero and Ilesha around where I grew up, which was even better (tasting) than the imported Thailand rice.”

When the government eventually restricted imported rice in 1980, the market price tripled. A bag of imported rice would arrive in Nigeria at a wholesale price of $52 and be resold at $180—about ₦99 at the time.

Through the economic decline, university tuition remained fully funded by the federal government. This meant Kayode didn’t have to worry about tuition or meal preparation at the University of Ife, where he was studying Agriculture and Economic Extension, in 1980. He only needed to take a 50 kobo meal ticket to the cafeteria, and he’d get a full-course meal.

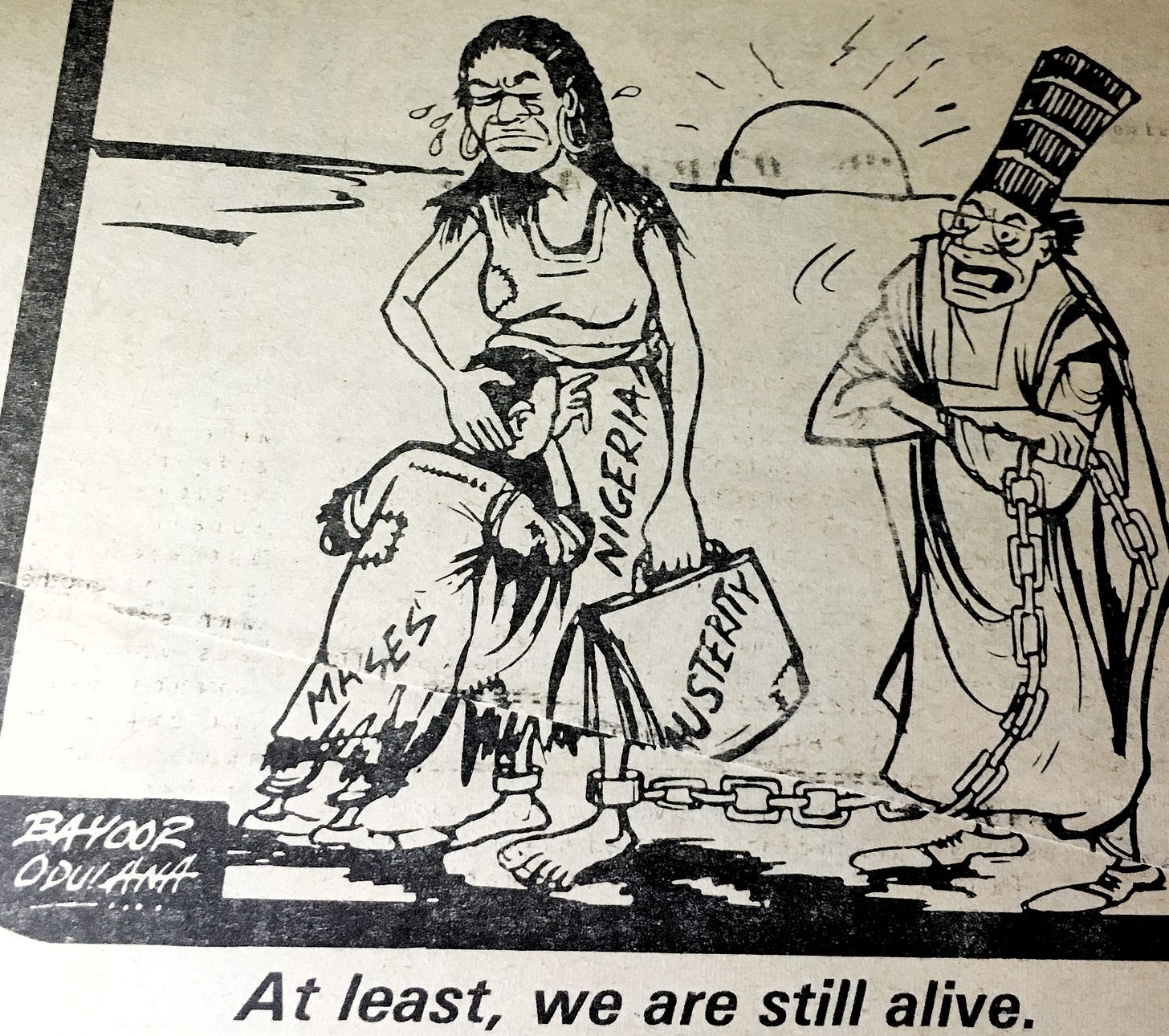

Towards the end of Shagari’s first term, just before the 1983 elections, the economy had gone into turmoil. The government tried to keep Nigeria afloat through an emergency stabilisation plan that cut spending. The federal and state governments halted new employment, and reduced imports due to foreign exchange shortages, leading to inflation in basic commodities and food. They halted the “Operation Feed The Nation” initiative that was designed to revive small-scale farming and pay students to farm during the holidays.

All indicators showed that Nigeria had already been driven to a dead end in economic, political, and social terms before the 1983 elections, but Shagari still wanted to run for a second term. In his campaign, he promised the basic needs of life: food security, effective medical care, electricity, water supply, housing, and industrial transformation—all the things he failed to do in his first term.

Kayode looked forward to change, and he believed that only Awolowo and the UPN could bring about change in Nigeria if they held power at the centre.

“We had it very well in the Western Region, LOOBO states, where Unity Party of Nigeria (UPN) was the political party in power. We had many of Nigeria’s firsts—the first university and polytechnic, the first government secretariat, the first television station, the first to use Ultra-High-Frequency (UHF) waves for quality TV sounds, and more.”

Kayode credited everything to Awolowo. He played a major role in the government’s decision to establish the University of Ife in 1961. He also built Cocoa House, a 26-storey building in Ibadan, which served as the headquarters of “The Nigeria Cocoa Marketing Board” until 1986, when the board was scrapped. The board used to buy cocoa from farmers, process it, and sell it to international buyers, and the profits made were used for development projects and initiatives.

On a warm Saturday morning, the day of the 1983 elections, Kayode lined up with students from different faculties at the polling booth in Fajuyi Hall's courtyard. When it was his turn to vote, he pressed his inked thumb on the ballot paper and cast it for UPN—Awolowo for president and Bola Ige for a second term as governor of Oyo State. Professors from Western universities openly supported the UPN, and to Kayode, “If notable academics here can be with Awolowo, why not join them.”

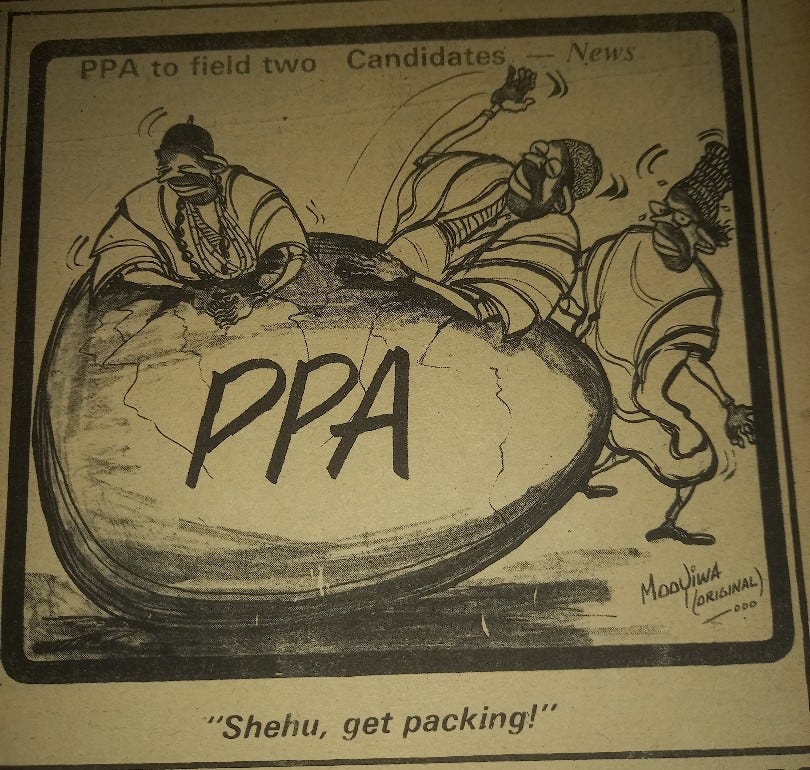

Throughout our conversation, Kayode kept referring to “The Progressives” and the ways that, in hindsight, they shaped his political opinions. The Progressives Parties Alliance (PPA) was an opposition bloc and political reform coalition led by Awolowo to transform Nigeria radically. They addressed concerns raised about the economy, government policies, corruption, transparency in the electioneering process and more–openly supporting national interests.

Kayode consumed proceedings from their meetings in newspaper bulletins. Leaders from different political parties were members of this coalition – Bola Ige, Adekunle Ajasin, Olabisi Onabanjo, Olusegun Osoba, Balarabe Musa, Ambrose Alli, Muhammed Goni, and others. The only hope for Kayode was to elect a progressive federal government.

He was sure every student in his polling unit voted for Awolowo. But what he saw that evening was a total reverse of what he confirmed in the morning: the results had been overturned in favour of Shagari’s NPN.

The 1983 elections saw the NPN clear 13 out of 19 states, including three western states Oyo, Ondo and Bendel, while the UPN won only Lagos, Ogun and Kwara. Kayode felt a rush of sadness, and it wasn’t just because Awolowo had lost but also because it made no sense that UPN had lost all of Oyo State too. The loss was nearer to him than the national level.

Awolowo described the elections as a tragic mockery. While the NPN called it a landslide victory, Awo's supporters cried foul, and violence followed. Kayode’s campus went into chaos. He saw Professor Wole Soyinka, a lecturer at the time, chasing a man everyone called 007 around the University of Ife campus in his Jeep because 007 was a member of the NPN. The police were also everywhere, intimidating and threatening people who dared to protest.

Riots broke out in various parts of the Western region. In Ondo, when their incumbent governor, Adekunle Ajasin, was defeated, UPN loyalists boiled. Ajasin had lost to Akin Omoboriowo, his former deputy who had crossed to NPN to become the gubernatorial candidate.

The day the Federal Electoral Commission (FEDECO) declared Omoboriowo the new governor, violence erupted in the centre of Akure, spreading to other parts of the state. In about a week, 40 people were killed in Ondo, and about 33 in Oyo, including two party congressional candidates who were reportedly set on fire by an angry mob. Eight election officials were burned to death.

Eventually, the country seemed to reach its own tipping point. On Saturday morning, December 31st, 1983, Kayode and every Nigerian with a TV or radio were dialled in.

“Fellow countrymen and women,” the voice over the radio began, “I, Brigadier Sani Abacha of the Nigerian Army, address you this morning on behalf of the Nigerian Armed Forces. You are all living witnesses to the great economic predicament and uncertainty that an inept and corrupt leadership has imposed on our beloved nation for the past four years.”

The military suspended the 1979 constitution, dissolved the democratic government, banned political parties, imposed a curfew, suspended flights, cut off international communication, closed borders and airports, and threatened martial law. A coup was in full swing.

On New Year’s Day 1984, Major General Muhammadu Buhari, the new Head of State, provided a rationale for the coup, stating that, “The corrupt, inept and insensitive leadership in the last four years has been the source of immorality and impropriety in our society since what happens in any society is largely a reflection of the leadership of that society." This new regime’s hallmark was a War Against Indiscipline.

Kayode welcomed the coup as a relief from unrest since the soldiers restored law and order, but his expectations of betterment were shattered when, in his final year of university in 1984, Buhari declared that the government could no longer afford to feed university students. “In my first four years as a student,” he recalled, “I only had to take a meal ticket to the cafeteria, and I would have a feast. Buhari came, and all of that comfort just ceased to exist. Feeding became a la carte.”

Buhari’s government ordered price control for essential commodities, and soldiers took over the streets, invading warehouses and shops to dictate the prices goods should be sold. It didn’t matter that inflation had hit the market. Soldiers with horse whips and rifles on their backs asked market women how much a commodity was sold and forced them to lower their prices. Despite the severity of the military enforcers, prices didn’t go down; things only got worse as traders began to hoard the goods to avoid selling at a loss.

Kayode had thought the Buhari-led government restored order, but it became apparent in 1984 that he’d only create more problems in every sphere of Nigerian life.

In 1985, Ibrahim Babangida, himself a veteran of several military coups and regime changes, overthrew Buhari for failing to end economic mismanagement, saying the government had been too rigid and unpromising. IBB promised to release all the Nigerian journalists and critics Buhari jailed, subsequently detaining him.

Kayode began to perceive IBB as a better leader, but he realised he had been sold a lie when IBB promised to return Nigeria to civilian rule nine times, and reneged every single time. Whenever Kayode heard him say “Insha Allah,” after promising on TV, he knew it was a lie.

When Kayode finished university, he was thrust into a wicked economic depression. He was convinced he had a shot working in a bank. Before leaving power in 1979, the Obasanjo-led government established a Rural Banking Scheme that mandated all commercial banks to open branches in rural areas. They also established the “Agricultural Credit Guarantee Scheme Fund” which allowed farmers to get loans to facilitate their operations, an opportunity Kayode felt his degree would fetch him working in a bank.

He had worked as a clerk at a First Bank branch just before enrolling in university, and that gave him more confidence to apply again after completing his mandatory service year. But the bank had no money to pay. That was when Kayode realised that no entity or government was coming to save him.

Life in Ṣakí, Oyo State, was gloomy in the 80s.

After Kayode's First Bank rejection and the many that followed, he moved to Ibadan in 1986. He spent the next few months finding new means to earn a living and exploring different forms of farming, but nothing seemed to stick. “It was one thing to be a farmer,” he admitted, “and it was another thing entirely to make profits from your farm produce.”

In 1989, IBB eventually declared a two-party system: the National Republican Convention (NRC), led by Bashir Tofa and the Social Democratic Party (SDP) by M.K.O Abiola. And in 1993, after postponing the election three times in three years, IBB finally decided it was time.

For Kayode, it didn’t matter if it was Abiola or Tofa, he just wanted IBB’s government out. Abiola had been a former member of the NPN, and Kayode remembered his Concord newspaper reporting anti-Awolowo stories during the 1979 elections. But the people loved Abiola, because he embodied the Nigerian dream, rising from nothing to contesting for the highest office in the country. In his manifesto, he promised to revive all the agriculture initiatives that had been cancelled, as well as the manufacturing industry, bringing back car companies like Volkswagen and Peugeot to employ Nigerians.

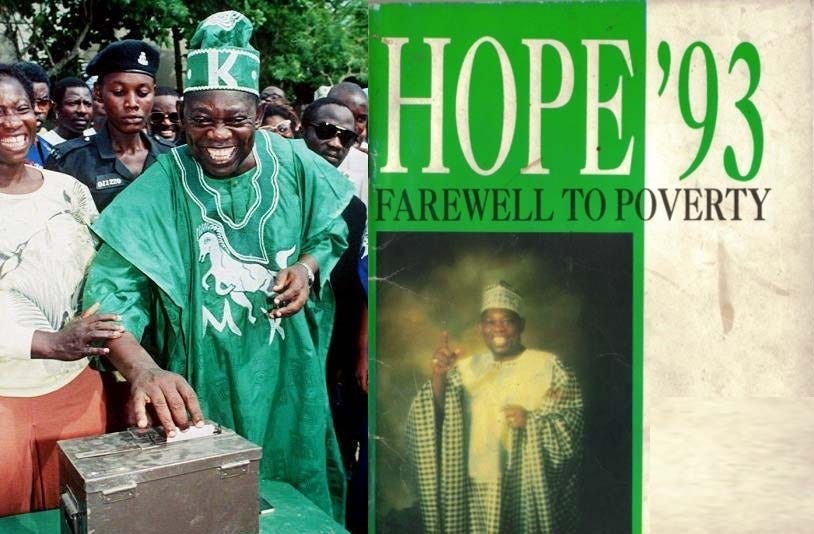

“That was why we called it Hope 93,” Kayode said, “Most of the progressives in the North and the South showed support for the SDP.”

By the time of the 1993 elections, Kayode, now 31, had gotten married and was with a child. The money he made – from trade or farming – never seemed to be enough, so he moved to Lagos for better opportunities. He ran a fishery consulting business with his friend while coaching science students for university entrance examinations.

It rained heavily on the night of June 12, 1993. Kayode considered it a sign; many people did. A new era had come that would finally bring peace and progress.

Earlier that day, he stood in line at his polling station in Oshodi. It was the Option A4 system, where people lined up behind their preferred candidate’s banners for a headcount, eliminating the need for ballot papers or boxes. Convinced that an SDP presidency would help him live off his true passion, farming, he stood in line to be counted for Abiola.

With the results halfway announced, Abiola had won 19 states, including Tofa’s home state, Kano. But a few days after the election, the NEC announced that the election results had been suspended.

Nigerians began to voice their disapproval quickly. Labour unions announced workers’ strikes, and student unions flooded the streets. Protests took place across the Southwest and even in the North, and they remained peaceful for a few days.

But the bubble broke in Lagos when thugs hijacked the protests, looting and destroying properties. They burned barricades, broke into shops, and burgled cars, and what started as a peaceful protest became an ethnic attack against Hausa and Fulani everywhere blaming them for the annulment because a Northerner was in charge. The protests ended the day after the military security forces intervened, killing scores of civilians all over Nigeria and arresting many more.

IBB refused to renounce the annulment. Instead, he stepped down and installed an interim government headed by Ernest Shonekan. For three months, unrest continued; the military saw another opportunity.

On November 17, 1993, 10 years after he addressed the country to announce a military regime, General Sani Abacha overthrew Shonekan’s government and delivered another speech. This time, he was going to run the country himself.

Kayode’s hopes plunged again.

Abiola still wanted to claim his mandate. With the backing of the National Democratic Coalition (NADECO), a broad coalition of Nigerian Democrats, he called on Sani Abacha’s military government to step down, declaring himself as the president of Nigeria. He was subsequently charged with treason and was detained for four years. It was only after Abacha died in 1998 that Abiola had any hope of regaining his freedom; he died the day he was to be released.

By this time, Kayode had moved back to Ibadan to run a poultry farm because the agriculture sector had improved during Abacha’s regime.

The new head of state, Gen. Abdulsalami Abubakar, organised new elections and oversaw a transition to democracy in 1999. After 16 years of living under military rule, former head of state, Obasanjo, jailed during the Abacha regime, was elected president of Nigeria under the People’s Democratic Party (PDP).

Kayode didn’t vote for Obasanjo in 1999 because of the stories he read about his term as head of state. In 1978, Obasanjo established the Land Use Decree which meant no one could own land, and everyone was now the government’s tenant by the law. Kayode also believed that Awolowo could have become president in 1979 if Obasanjo wasn’t against him. The military, Kayode believed, backed Shagari and the NPN. To him, It seemed like Obasanjo had sworn an alliance with the North and wouldn’t prioritise the South.

Instead, he voted for Chief Olu Falae, an economist from Akure and a Yoruba man. He believed Falae could have carried out good economic reforms for the country. Progressives like Bola Ige, who was a columnist with the Tribune, were also against Obasanjo, forming public opinions about him. The progressives used to draw comparisons from other countries, envisioning what Nigeria could be if specific measures were implemented. Kayode would scour several newspapers for their ideas. Without intending to buy and take the papers home, he’d pay about 5 kobo, read, discuss with others at newspaper stands, and place them back on the vendor’s table. Since he moved back to Ibadan in 1993, he’d do this every morning to read what the progressives had to say in Daily Times, Sketch and the Nigerian Tribune.

But in 2003, when Obasanjo wanted a second term and his major opposition Buhari, was a Northerner, Kayode said, “He’s our own (Yoruba man); let him do it.” Obasanjo won. To Kayode, Obasanjo was fiscally disciplined with the nation's affairs as he was in 1979. “That’s the reason our debts were forgiven,” he said.

Kayode’s life also began to pick up.

He coached science students and ran his poultry and fishery businesses at a scale larger than he’d ever been able to accomplish before. “When the economy is thriving, it’s easier to do business. I found my bearing,” he said “I could plan my finances, and didn’t have to worry about my children’s school fees.” This was the time he got his first car, a Peugeot 504.

By 2007, Kayode was excited to vote. What stood out for him in that election was that Yar'Adua had a Master's degree in Industrial Chemistry, which meant he had great analytical skills. Yar’Adua was the first university graduate to become president of Nigeria. “He wanted to reform the Land Use Act. The man had good intentions for Nigeria, but didn’t live long.” Before Yar'Adua's 2010 death upended his government, Kayode bagged a Master's in Agricultural Chemistry in 2009.

In 2011, he voted again. This time, for Goodluck Jonathan, who he later considered unprepared for the position. “As his administration progressed,” Kayode recounted, “the PDP had become a monster, looting left, right and centre.” His government was also criticised for its slow response to the Boko Haram insurgency, depletion of the foreign exchange reserve and an attempt at fuel subsidy removal. Buhari never stopped running for president since he started in 2003. Ahead of the 2015 election, Kayode recounted, his campaign, and the media presented him as the saviour: a morally upright man who was disciplined, frugal, and everything Jonathan was not.

But Kayode had no fond memories of his dictatorship in 1984, so he voted for Jonathan in the 2015 presidential election. When Buhari was declared president, Kayode felt betrayed by everyone and decided that was his last straw: he’d never vote again in a Nigerian election “I have seen all these leaders inside and out, there’s nothing they have to offer me,” he said. And so, after actively participating in Nigeria’s electoral process for 40 years, Kayode stopped voting.

My heart sank a little as he said, "Even the local election they did in my backyard last week, I didn't go. I won’t vote again." It felt like an exercise in futility as I wanted to hear insights that would prepare my mind for the next presidential election. Instead, I discovered his now profound disillusionment with the political process. 40 years of casting ballots had yielded neither strong leadership nor economic growth for the country. The once-burning optimism of the 17-year-old boy in Saki had been quenched.

It was stirring to watch Kayode bustle around the small walls of his school, coordinating the students. It was their lunch break when we visited. He explained that he founded the school in 2012 as a small effort to give back to the community. “The essence of knowledge,” he said, “is to navigate the circumstances at your disposal, and use them to your advantage.” What started as coaching sessions at his veranda, had grown into a school. As he sat across from my friend and me, in his Ankara prints, his eyes burrowed deep in mine, and he sighed, praying we never have to witness the economic depression he was subjected to in 1986.

When Kayode last voted, I was barely a teenager casually vocalising, “Sai Baba, Sai Buhari!” I heard it repeatedly over the radio, every morning while commuting to school. My parents and the adults around me actively endorsed his change mantra.

Buhari was our new messiah. I was told he’d save the Nigerian economy as he did in 1983. He’d also release Nigeria from the constraints of the PDP’s 16-year rule. I stayed glued to the TV as INEC collated the results all evening. When Buhari won the election and was inaugurated as the new president, I was happy and certain it was an era of change.

In 2019, Nigerians gave Buhari a second chance after he argued his efforts only amounted to helping the country out of a ‘depth of decay’ and then a foundation, which, if re-elected, would serve as a basis for a stronger country – the next level. He insisted he had not reneged on the promises he rode on to win in 2015: security, economy and anti-corruption.

But when Buhari refused to condemn the attack on the young Nigerians in the 2020 #EndSARS protest, I was 17 and began to see him for who he truly was. In 2021, he suspended Twitter access in Nigeria after a tweet from his account was deleted for violating rules; it felt like a reincarnation of his Decree 4 of 1984.

When I asked Kayode, now 62 years old, what he was hopeful about these days, he said he only wants his school to one day serve a greater purpose. If he had his way, the students wouldn’t pay school fees, but the times continue to be hard in Nigeria. As with most senior citizens I’ve spoken to, Kayode was happy to tell us stories from his life while we listened. As he walked us to the nearby junction, he continued recounting his experience.

It was when I settled into a bus after I reached Lagos that Kayode’s life began to properly register. When I went to Ibadan, I knew little beyond the headlines I’d seen or books I’d read. I returned to Lagos weary from the long day, but awake to what feels like a new reality.

I began to think through Kayode’s choices and the factors that influenced them: the media, his strong attachment to his tribe, his sense of intellectual belonging, etc. He participated in eight elections, and his desired candidate only got in thrice. For every time he tried and they didn’t get in, he could only imagine what could’ve been.

I could feel anger brew in my chest as I entered my home in Gbagada. I wondered how many people across the country stopped voting because they believed it wouldn’t count. Of the 87.2 million Nigerians who obtained their permanent voter’s card (PVC) before the 2023 election, only 27% got to decide who became the president, and I wasn’t one of them. The president, Bola Ahmed Tinubu, won by a narrow margin with 36.6% of the total vote cast. His major rival, Atiku Abubakar, polled 29%, and third-placed Peter Obi, with 25%, even won Lagos State where Tinubu had an eight-year reign as governor, with a string of successors who gained his approval first.

The only election with vote percentages this close was 1979, when Shagari cleared 33.7% of the total vote cast, while Awolowo polled 29.18%. One thing was certain: regardless of whether I voted, the leaders in power held the ability to shape my life and our nation’s trajectory for decades to come—this remains a constant source of dread. As I count down to the 2027 election cycle, I continue to sit with the consequences of my indecision.

It Took A Village (and a lot of time) To Bring This Together

Finally publishing this story brings me immense relief. It's been six months since I started researching - the longest I've ever spent on a story. This is also the most complex piece I've ever written.

The first challenge was deciding what story to tell. How do I tell a story about what it means to vote in a country like Nigeria and make it meaningful to me?

My editor, Fu’ad, asked me to start talking to people. And that’s what I did. In between speaking to over a dozen people, travelling, and becoming a regular library visitor, It felt like I was onto something.

One night, I decided on a whim to visit Kayode in Ibadan, and that changed everything. It was a turning point, and it was there that I gained the clarity I needed to ground the story.

It took four drafts and countless revisions until it finally felt right. On the road to the first draft, besides Fu'ad's rigorous editing, there was Afolabi asking very tough questions about why this story should even exist. There was Samson, who’s covered the last two election cycles, interrogating my perspective. I'm grateful for them. Aisha Salaudeen constantly pushed us to get this story to the finish line.

I like to sketch, and so, it was great to work with artists to sharpen my sense of art direction; I’m grateful to Mariam for that. Also, Penzu for the character illustrations, and Kenny Owolawi for bringing the infographics to life.

I've learned that one story can lead to many others, and ideas can grow from a single question. I'd never written about politics before, but now I have a wealth of information to explore.

I'm grateful for the interviews, especially the one with my grandma; it turned out to be our last conversation.

Family, friends, and colleagues gave me many pointers. They shared their knowledge, referred me to people, and endured my endless chatter about the story. I especially appreciate Muhammed Bello for following me to Ibadan at such short notice.

This story exists because The Election Network commissioned a story—a “just explore it” story—about what it means to be an electorate in Nigeria. Vistanium found an angle true to its values and curiosities. Most importantly, Vistanium’s members continue to back experiments like this.

This story is deeply personal and significant to me. Hitting publish felt emotional. My political awareness has improved dramatically. I began with a limited understanding of Nigerian politics, but now I have a clearer grasp of how it works. Still, there’s so much to learn. This story has helped form the basis of my political perspective.

Thank you all for helping me bring Ballot Ballads to life.

This piece really resonates with me. It was like going through Kayode's experiences myself, and I could empathise with him. 🥹

The story was beautifully narrated.

Many thanks to the village for their time and effort!

This is a result of rigorous research. I am amazed at the unearthing of publications of the 90's and also the historical references.

I love your story writing technique, the way you flow it with Kayode's story from his teenage years to his 60's.

I feel like a time traveller reading this.

The pictures and illustrations are beautiful, it sheds more light to the story.

Kudos to the team that made this attainable.

Overall, I love you. You're a star and an inspiration. I would love to read more from you and most likely work with you.

Muchas Gracias.