At a mechanic’s shed somewhere in Lagos, Funmi lay down on a bench to take a nap.

He looked like a groomsman at a wedding with his white satin bùbá and ṣòkòtò. But that day in 1992, he wasn’t dressed for a wedding. Instead, it was for the mechanic – he was having one of those “I’m not leaving here until you fix this car” days after too many “the carburettor done spoil” ones.

He’d been lying down long enough for everyone to think he was sleeping when a man came to the shed.

“Who owns this white Pajero,” the man, likely in his late fifties or early sixties, asked in Yoruba.

“It’s that man lying down there,” the mechanic replied.

“That one?”

“Ehn.”

“Ah,” the man sighed, “God, please make my son too successful like this boy o.”

Funmi smiled and thought, “Look at this man praying for his son to be like me, without even knowing what I do for a living.” The first time I heard this story from Uncle Funmi, someone had just said something about a small aspiration I can’t even remember.

It was a funny story then and still is because at the time he was in that white bùbá and ṣòkòtò and drove that white Pajero, he was 28. He was also a full-fledged, bank-bursting, car-snatching, gun-wielding armed robber.

—

But at the time I heard this particular story, ahhing and laughing, almost a decade had passed since that day at the mechanic’s, and he’d become my lesson teacher.

Uncle Funmi was dark and tall but hunched a little, with a thick build. On many weekday evenings in ‘99 and 2000, he was either teaching me maths tricks or helping my brother navigate Accounting and Economics. But his lessons didn’t end with school subjects. He was also my teacher for the little things.

“Lekan, write on the line,” he’d say about my handwriting, “and don’t let your words fly up to the line on top of it. Instead, let them stay on the ground with the lower line.”

The first time I wrote in a straight line, I was eight, and he was there. We celebrated with Sprint chewing gum and Coke. He also showed me how to make a blackboard gone white with use, black again.

“Grind the charcoal and pour in small water,” he explained, “then make it thick like you’re making pap. Use small foam as your brush, and then use it to paint the board.”

As for chalk, we never bought those; we just picked them from the ground outside, white or pink. When the diggers didn’t know what to do with the chalk-filled earth they’d excavated while digging our well in 1998, they just levelled our compound with it.

“Just pick the dry ones,” he’d say, “but not too dry, so it doesn’t make that scratching sound on the board.”

He spoke well, was funny, and every quiet sigh was a sign that a gang life story was coming, so we paid attention. He ended every story with, “But make sure you listen to your mother, no matter what,” or he’d say “ka ṣaà ma ṣe daada,” let’s just continue to do good.

His primary audience was my brother, who was almost twenty, an aunt about that age too, and whichever cousin was staying over at our house. I was hardly ever in the room when he told these stories, but nothing misses a curious ear in a small two-bedroom apartment. I could hear a conversation happening in the bedroom while I did the dishes in the kitchen. And if I sat on the chair closest to the living room window in the evenings, I could hear him outside telling my dad stories over Rothmans or Benson and Hedges.

His gang had no leader; every operation was led by whoever brought a lead forward and had a plan. Uncle Funmi preferred operations that started and ended fast, like highway robberies. On the other side of the gang was Owo – we’ll call him Owo because I can’t remember his name. Owo was a short man who loved to make big statements.

One time, they robbed an office building and were leaving with a lot of cash. “We needed an extra vehicle,” Uncle Funmi said, “So I went to the road, stopped a car and asked the man to come out,” but the man panicked. “Come down o, this person coming is a mad person!” Owo just walked up to the car and shot the driver in the face. They all drove away in the car with bits of the former driver’s brain still splattered across the seats.

Another time while robbing another office, Owo demanded that a man hand him the keys to wherever it was they kept the money. The man, too panicked and confused, kept pleading for his life. Owo walked up to the man, grabbed his head with one arm, and slit his throat with a knife in his other hand.

This streak made Uncle Funmi uneasy about their last operation together. “My spirit didn’t go with it,” he said, “I thought it was too dangerous, but he didn’t listen.” And so, Uncle Funmi didn’t go.

In September 1992, a policeman argued with a driver at a checkpoint on an island exit of the Third Mainland Bridge. The argument ended when the policeman’s rifle coughed seven times and the driver lay dead on the road. The driver was army colonel Ezra Dindam Rimdan.

For fear of reprisal attacks from the army, police officers across Lagos withdrew from all checkpoints. As a result, armed robbers around Lagos had all the lee-way to pull off the kinds of attacks Owo was leading. This crime wave led to the creation of the Special Anti Robbery Squad, SARS, in November 1992.

It took a little over a year, but that squad of police vigilantes eventually caught up with Uncle Funmi’s gang – it also happened to be the operation he didn’t go on. At their head was Owo.

At first, Funmi wanted to lie low and hoped none of them would snitch, but the police came looking for him eventually. When the police come and they don’t find you, they tend to take someone back with them as leverage. And for Funmi, they took his frail mother.

He surrendered himself to the police shortly after.

In court, they were all found guilty and sentenced to death – all of them except Funmi. Despite the torture, he pled not guilty because he was never really caught robbing.

Owo and the rest of the gang were sentenced to die, but although Funmi’s lie kept him alive, he was held in Ikoyi Prison while awaiting trial.

—

When Ikoyi Prison was first built in 1955, it was designed as a federal medium-security facility designed to hold 800 inmates. But when Funmi showed up at its gate as an inmate awaiting trial, he was one more body sardined into a yard with over two times more people than the original capacity. Getting into Ikoyi Prison in the mid-nineties, he’d have been sharing the yard with all kinds of people; rapists, murderers, other armed robbers, politicians, activists or moguls guilty of fraud or incurring Abacha’s wrath.

But in spite of the suffocating conditions of prison life, there was newfound hope for Funmi. A relentless lie had earned him a second chance at life. The first thing he rediscovered was faith. Then, he picked up education where he’d left it – preparing for his senior WAEC exams. An NGO, The Good Shephard Community, covered the costs, and it paid off – while in prison, he enrolled to write his WAEC, and he aced it. He did so well that it played a pivotal role in the next thing he was seeking; freedom.

Over half of his fellow inmates were awaiting trial, some of them for up to a decade. Too many things must align for an inmate awaiting trial to get a day in court. First, you’ll need a lawyer, most likely working pro bono; a means of transport to the prison, most likely provided by an NGO or church; a court not on strike, and a proactive prison officer willing to organise these people around the problem.

The prison officer in charge of Funmi’s case was my mum.

I spent a lot of my holidays in primary school and early secondary years following her to work at the prison. It’s where I also encountered some of the most interesting characters in my life. There was Lanre, the soft-spoken armed robber who spent all his free time in prison wearing boxing gloves and sparring with anyone interested. There was a man who, when I asked him what he was replied, “I’m a banker.” When I asked my mum why he was there, “Fraud,” was her answer. There was Brown, who worked at a restaurant until he punched a person at a party and ended up in prison because the person on the receiving end died shortly after the knockout.

The outcome of her work meant many things to me as a child in all kinds of ways; big, small or just random.

It was being stuck in traffic, a random agbero coming out of nowhere and clearing traffic for her to drive through. He was calling her mama, giving her the twale and a thank you, while refusing the tip she offered him.

“Where do you know him from?”

“I don’t know,” she’d say, “he was probably in Ikoyi Prison at some point.”

It was visiting a brothel on Stadium Road, Surulere because my mum had to meet with the girlfriend of an inmate whose release she was trying to facilitate. It was someone coming to visit us at the house a second time, with a cardboard model of our home as a thank you gift – he learned the layout of our house by simply going to pee during his earlier visit. I asked him how he did it, and he said, “I’m an architect.” After he’d left, I asked my mum how she knew him. “He was in Ikoyi Prison for drug trafficking.”

One day, a “thank you ma” visitor came in a deadbeat Skoda that should have been navy blue, but for the rust on many parts of the car.

That visitor was Uncle Funmi. It was the first day I remember him ever coming to our house. Out of the car also came his wife and their two daughters; the older one was about my age – he’d had them before going to prison.

Almost four years after he first got into prison, Uncle Funmi became a free man again shortly after General Abdulsalam Abubakar, Nigeria’s last military dictator, got into office in 1998. He talked a lot about the people he had to thank the most; The Good Shephard Community and my mum. And because of how indebted, he came around a lot, looking for how to help out or be helpful, till he eventually felt like family.

It’s why, for example, he was teaching me maths, and my brother maths, economics, and accounting. Nigeria is not kind to the conventionally qualified, and it’s even more unforgiving to the previously incarcerated – especially when you’re poor and powerless. But here was Uncle Funmi, trying to build a new life on the straight.

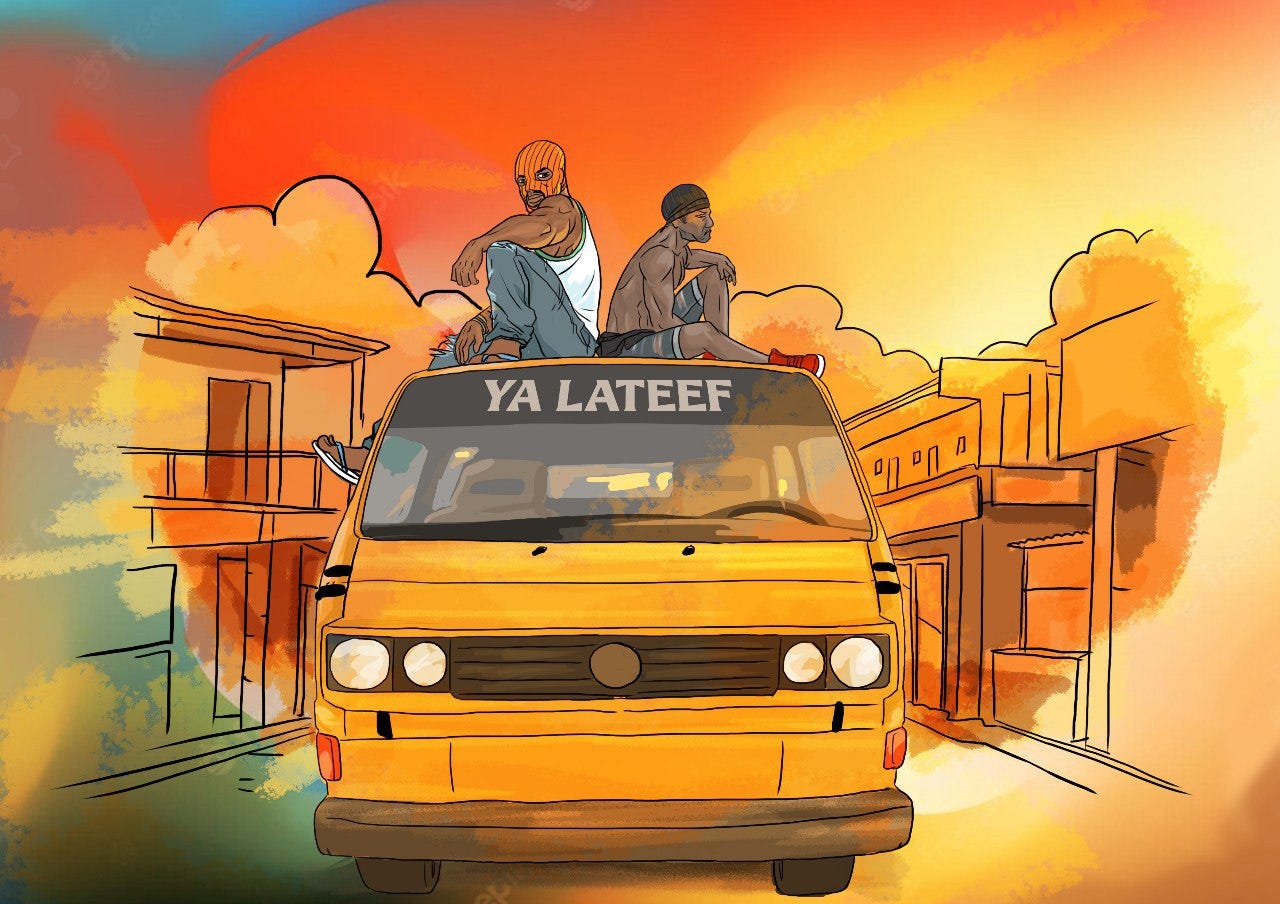

He was teaching evening lessons at ₦50 a class, but it wasn’t enough to make a living. So he was making other plans too. One weekend, he showed up at our house with a Faragon Danfo he’d charmed an owner into leasing to him. He was saving everything he could for his next big plan.

Later that year, Uncle Funmi showed up with good news; he’d gained admission to study Economics at the Olabisi Onabanjo University in Ogun State. But because he still had a family to care for, he knew he still had to make a living.

He wanted to raise enough money to start a small business near the campus.

When he showed up one weekend in 2001, it was the last time I saw him with the Danfo. Driving the danfo for a few days and returning to Ogun State for school wasn’t working out, so he handed the keys back to the owner. But that day, a large photocopier was at the back of the bus; he’d bought it with money he saved up driving the bus, teaching, and the generous hundred nairas here and there.

“It’s a student environment, so everyone is going to need to do photocopy,” he said. However, he had nowhere to keep it, so he just kept it under our bed. “There’s no space in our self-con to keep this,” he said. He’d pace a lot whenever he talked about his plans with feverish excitement and nervousness.

He dreamed about the standing fan he would buy and the kiosk he would rent. Ahh, a generator; he was going to need a generator.

Things were looking up, and they did for a while until they didn’t.

One Thursday in 2002, my parents returned from work to an empty home. Someone didn’t lock the door, and a bowl of garri was sitting on the centre table in the living room. My brother, who they were sure was the one who left the bowl on a table in the living room, was nowhere to be found. The first time I asked my brother about that night and the bowl of garri, he laughed – it’s funny now.

“It was the day after my ATS II exam for ICAN,” my brother said; no one was home. “I just said I should soak garri o.” So the garri got in the bowl, followed by the sugar with groundnuts. And just as the water was about to go in, there was a knock at the gate.

“By the time I was going to open the door,” he said, “they already opened the gate. The first person I saw was Uncle Funmi’s wife.” Two plain-clothed men behind her, armed with rifles, marched into the house, pushing him out of the way.

Before he could greet her at the door, she pushed past him at the door. Behind her were two men in plain clothes. She walked through the living room and straight to the bedroom. Then she pointed to the photocopier under the bed, “Funmi lo ni photocopy machine yìí.” No one knows why to date, but evidence of his property in our home was all the justification the police needed.

No one said a word to him, they just grabbed him, and took him to the waiting bus outside. It was in the bus he realised that they were in fact, policemen attached to SARS.

“It was SARS,” my brother recalled, “and you know how they are. No one said anything to me, but I could tell it was about Uncle Funmi. And as long as it was about that, mummy was going to fix it.”

A few hours later, he was in a police station in Ijebu Ode, stripped to his under shorts. “They put me in dark cell,” he said, “but I could make out someone else in the cell, it was Uncle Solo, remember him? The one that used to come with him sometimes?” I did remember him, but before I could even respond, he said, “the one that used to come to the house with Uncle Funmi when they had danfo? I met him in the cell. He was begging me to beg the police officers not to kill him.”

Every night for the next two nights, they’d take Solo out of the cell, torture him, and return him after a few hours. When they took him on the third night, he was never returned.

After my brother’s first night at the police station, my mum and dad showed up to secure his release, but they didn’t succeed. And so it was that he spent two more nights, while they called everyone they could. By Monday morning, they were going to release him, but on one condition; they were going to swap him with my mum.

My mum spent one night in detention, and the DPO was gracious enough to convert his office to her holding room; she was his ranked superior. Detention is demeaning, but for his gesture, she was grateful. She spent one night.

I returned home from boarding school two Wednesdays later, a midterm holiday. On Thursday night, my mum was seated in the corner of our living room after the Isha prayer, the TV was on. And as the news came on, my dad increased the volume.

The AIT news anchor talked about an incident in Ijebu Ode, Ogun State. The news cut from the studio to a road. The anchor broadcaster was talking over footage of bodies lying on the road; the Police in Ijebu Ode had killed armed robbers after a shootout in Ijebu-Ode. I counted two bodies. Everyone knew what was coming.

We were huddled in front of our TV, my mum, off the mat now, and beside me.

My brother was back in the living room when my mum called out to him. Next came an aunt who’d come to stay with us for a few days.

My brother was the first to see his body in the news; he looked like he’d died of beating instead of actual bullets. “Ah, see Uncle Solo.”

“One suspect is still wanted,” the reporter continued, “Funmi Ajayi, a 300-level student of Economics at Olabisi Onabanjo University.”

—

Two things meant a lot to my mum; her personal relationships and work. Everyone says she carried both of them really well. But as a child, it wasn’t always easy to tell them apart; what or who was work, and who was familial? So many nights, we’d be watching TV after dinner while also sorting out paperwork.

“What are these papers for,” I asked once.

“Amnesty,” she replied, “sometimes, governors want to grant amnesty, and part of my job is sorting out the paperwork for inmates and making sure that their case is strong enough for them to be released.” The repentant, the promising, the overstretched awaiting trial inmate, the sick. The first time I saw HIV on paper was for an inmate who was well-behaved and needed to be closer to better care on the outside.

“Just put one paper here,” she pointed to a stack, “then put another one here,” and then another, “this one is for the governor’s office, this one is for the ministry of justice, this one is for the Controller’s office.”

Work remained a constant presence in her life, and my childhood felt like a part of both. So I’d be catching up with my classmates about what we were up to at home, and they’d be saying they went to the beach, and there was me saying, “Last holiday, I saw Clifford Orji the Cannibal.” My classmates were divided into people who said, “did he try to bite you,” and “why you too dey lie?”

I learned to play chess with pieces hand-carved by a condemned criminal, made in the carpentry workshop, one of the vocational workshops inside Ikoyi Prison. My mum bragged about my primary school grades, so he made me a chess set as a gift.

—

After that April in 2002, just as Uncle Funmi had remained wanted, he disappeared from our household, not just in presence but in chatter. After that, we hardly spoke of him. On the few occasions his name came up, it was because someone claimed they’d spotted him somewhere.

“Someone said they saw Funmi in traffic on Ikorodu Road,” my mum said one day.

“Do you think it’s him?” I asked.

“I don’t know.”

Fast forward a few years later; Independence Day, 2006.

My mum was in the kitchen making breakfast. A +44 number was calling her, and she stared curiously, trying to figure out what country the call was coming from.

“Hello, ma,” the voice on the other end said.

“Hello?”

“Emi ni, aunty mi,” the voice said. The person on the other end was a year older than my mum, but he called her aunty mi when he was in prison, and even as a free man.

“Funmi!”

Weak at the knees, “I just sat on the floor of the kitchen,” she told me. He was calling from Europe. There was anger and a long rant. Finally, she hushed as though speaking out loud would endanger anyone nearby.

Over the phone, and after all his sorries, he told her his story of what happened.

Ago-Iwoye is an ancient town with many young people, mostly Olabisi Onabanjo University students or people pretending to be students. It’s part of the old Ijebu Kingdom and a thirty-minute drive from the seat of the Ijebu throne in Ijebu Ode.

Word had reached some powerful people in Ijebu Ode that he’d crossed in his robbery days that the notorious Funmi was out of prison and at Ago-Iwoye. The first group they set loose on him was the OPC, a Yoruba-interest group that’s everything from a political organisation to a vigilante group, depending on the stick you draw. Funmi drew a bad stick. Then SARS came next.

In just a few days of word spreading, the new life he’d been trying to build fell apart.

The first people the police picked were his friends, some old acquaintances from his prison days. One was Solo, whose body we’d seen in the news. And then, slowly, he felt the walls closing around him, with a few hiding places and even fewer people to trust.

His final straw came one day, a few weeks after the AIT news broadcast we all watched while he was hiding away in his friend’s house. On a pure gut feeling, he stood up to leave, and as usual, he had no plans to go through the front door. Just as he was scaling the fence in the backyard, he heard the voices of the OPC men entering the compound.

“I didn’t know what to do again,” he said.

I imagined he probably sat by himself and stewed in it all. His old life as an armed robber, almost dying as violently as he’d been living. About how prison, despite its many inadequacies, had shown a path to redemption for him. About leaving prison and trying to start a life. I imagined that he thought about how he just couldn’t catch a break. About a marriage that was doomed from the beginning, and the two kids he had as a young man, the ones would come into an existential awareness of him while he was in prison. I imagined him feeling like he knew he could be better, that he was capable of doing better.

Then the moment he realised that to completely set himself free forever, he had to make one last run, just like in the movies. He went back to do the one thing he was great at besides maths; robbing. “They’ve kuku said I’m an armed robber already, so nothing spoil,” he told my mum.

Getting a weapon was easy; the hard part was robbing alone. Still, he did a few robberies, raised enough money, and fled the country. He tried to start a new life in Europe.

His call was to apologise for everything she’d gone through. Reaching out sooner, he felt, would put her at risk further.

“I’ll never return to Nigeria,” he said, not till further notice at least.

But people who work in security and defence hear things and know things. And so one day in the late 2000s, my mum got a call – this one came from someone at the Department of State Services. I was sitting right beside her when it came in.

I saw her face wrinkle in worry, her tone filled with concern.

“They found Funmi again,” she said right after the call.

“As in, they found someone that looks like him?”

“No, they found him this time,” she sighed. He’d come back to Nigeria to get better papers and somehow triggered a red flag at the embassy. His name came up on a wanted list, so they handed him to security forces.

“They’ll hand him to SARS, but he’s never going to make it to court,” she said, “wọ́n ma paá, because he’s already put them through too much trouble.” I’ve heard stories about people who end up with SARS and never make it out of their compound.

My mum was sure that he was already dead.

-

Despite everything, my mum, dad, brother, and I retained a collective fondness for him. My brother, an investment banker, considers him one of the most intelligent men he has ever met.

“He saved my life once,” my brother said.

Early in 2000, my brother had just stepped out of the JAMB office with Uncle Funmi by his side. Uncle Funmi passed his exams. My brother didn’t.

There are few things worse than getting stuck in limbo with Nigerian parents because you can’t get into university.

“That day,” my brother said, “I just kept walking, thinking about all the things I would hear when I got home. I didn’t even know I’d walked into the middle of the road. Na Uncle Funmi pull me commot just as car be wan jam me. He said, ah, don’t let this delay make you kill yourself.

Sometimes, I think about how the person Uncle Funmi was in his stories was a criminal with a conscience; Mr. Ethics. The robber who didn’t kill and even tried to protect innocent people from his gang. The man who only went back to robbing because he had no choice. He probably wasn’t lying because he didn’t lie about other things, but he also probably never spoke the whole truth, and I’ve made peace with that. It’s like it was important to him how we perceived him; I understand it.

I don’t know anything about his childhood, where he grew up, and the circumstances that led to his choices. I think about action and consequence, rehabilitation and relapse. About what could have been and never will.

I remember him as an armed robber who put the fear of the dark and lonely roads in people’s hearts, and his legacy will live on in people’s PTSDs. But I also remember him as my maths teacher, our storyteller, the kind of uncle you could tell a secret, and who didn’t make you feel small.

And so, even when all good reason says he’s dead, a small part of me still believes he’s alive and made some sort of great escape. These days, that tiny speck will come alive when I see a little child hunched over a notebook and grabbing a pencil or a pen. I’ll get closer and look at what they’re writing – it’ll be ruled paper and their words will be flying up.

I’ll squat beside them, hold their hand steady, and say, “write on the line.”

This story was dragged to the finish line by a small village:

Ruka, who gave the first draft all the disdain it deserved. She never fully recovered from that first draft.

Ope, who copy-edited part of an early draft. Dami caught a typo in a final draft. Hassan and Toheeb caught one thousand final-er draft.

Samson, who gave it the first sleeves-up treatment, top to bottom.

Then SI, who copy-edited the hell out of it.

And Anita, who came with some last-minute critical feedback

where I just told her to eat shitthat I’m thankful for.The illustrated portrait of the masked man in front of a blackboard was made by the art-rendering AI at Midjourney. I shared my prompt with Justin, and after a few iterations he made to my prompt, we landed on this portrait.

All the remaining illustrations were made by Penzu.

Most importantly, this story became a thing I wanted to explore because of this thread:

I once knew an Armed Robber with this type of 'ethics'. He used to say that as a rule of thumb, the person who identifies the operation will direct it. His own operations had clear rules, no killing. Just take their things and go. 1/Imagine Ogogo robbing you and still sympathizing with you. He is such a perfect gentleman 😍 https://t.co/2Y7475xA0o

I once knew an Armed Robber with this type of 'ethics'. He used to say that as a rule of thumb, the person who identifies the operation will direct it. His own operations had clear rules, no killing. Just take their things and go. 1/Imagine Ogogo robbing you and still sympathizing with you. He is such a perfect gentleman 😍 https://t.co/2Y7475xA0o Akin Akinwale @mrlurvy

Akin Akinwale @mrlurvyI always thought it was Germany that he fled to – that’s what’s in the Twitter thread – but my dad insists it was London. Thanks to that man for answering my silly questions like, “what cigarette did Uncle Funmi smoke?” My brother too, for his patience when I was constantly asking him, “what were you feeling when they came to carry you,” and him saying, “I actually wasn’t scared” over and over.

And of course, my mum – bless her soul – for being such a great role model for selfless service and work-life balance. Ha.

What an amazing and interesting story. It gave me the feeling that novels like Nwaubani's I do not come to you by chance and Imasuen's Fine Boys gave me, stories that made sure I saw people and the Nigerian condition as the multifaceted and complicated things they are. Thank you Fu'ad and everyone in the small village.

This was a really good read. Society often condemns people who commit crimes but life really isn't black or white. I liked that this showed Uncle Funmi as the main character in his story. Thank you Fu'ad and the village for bringing this to life!