A Northeast Travel Guide For The Unhinged

Or Unencumbered. Filed Under: Pulse36, Travel

Friday, August 4, 2017

It’s a few minutes past noon, and this is when shit starts to get real. We’re in an office with a bench for a seat. – four of us are seated on it – Jesuloba, Chris, Mansur and me. To our left and right are two wooden windows – when they swing, the hinges cry gently.

A man is seated behind a table facing us, and I can’t tell if he’s smiling or his face just looks like that. Let’s call him Mr Smiley.

There are two people behind us.

“That’s why I brought them here,” one of them says. He has just explained everything that's happened in the thirty minutes leading up to this moment. Mr Smiley thanks him and dismisses him. He shuts the door behind us.

The other man behind me is quiet, uncomfortably – Mr Quiet.

“Who’s the leader of this group?” Mr Quiet asks.

“I am,” I say.

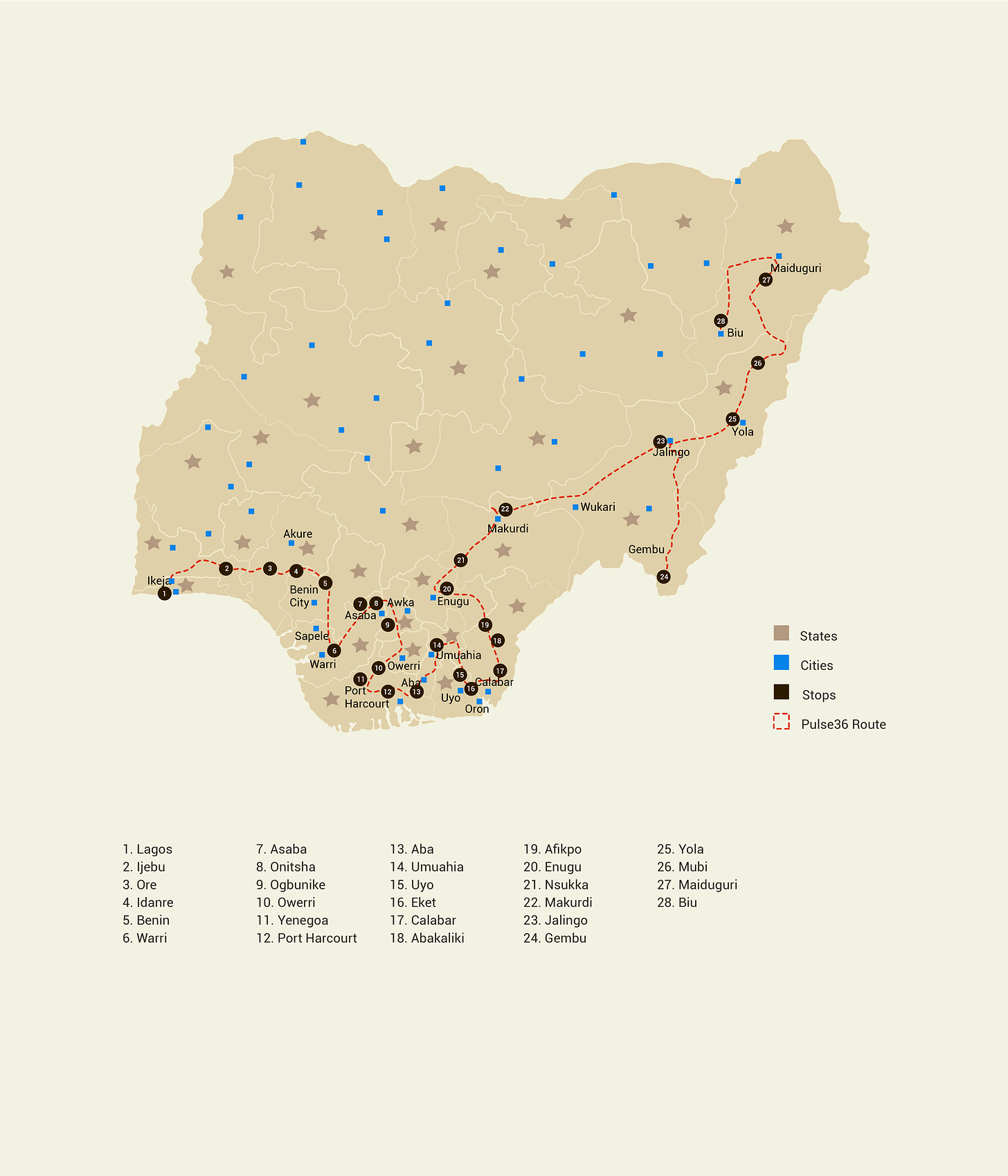

On New Year’s Eve of 2016, I told my Editor-in-Chief at Pulse about my strongest itch. “I want to travel around Nigeria in one stretch, every state.” He thought I was mad, but he was just as mad, so he told me to come up with a plan. Two weeks later, I presented him with an itinerary outlining everything I’d be doing on the road for three months.

“Fantastic,” he said, “we’re doing it.”

I worked at Pulse, a newsroom in a media company with a little less than 200 people. For the next few months, I tried to get every unit to buy into the project by selling them their benefits. Sales could get sponsors. Editorial could get content. The first day I was supposed to travel was in March – it got cancelled. While I was dealing with not travelling, I wandered into an exhibition on one of my night gallivants. Fati Abubakar, a photographer from Borno State, was exhibiting photos from everything she’d seen back home.

It’s while I was telling her about the road trip I wanted to go on that someone overheard me and went, “I want to come! Abeg.” He was wearing a scally cap and had a camera in hand.

He talked about a trip he’d just finished with photographers, where they travelled across some parts of Nigeria by train, taking photos everywhere they went. I told him I’d be travelling for work, but he promised he’d never get in the way of any decisions I was making for work — the more, the merrier.

“I’ll keep you posted,” I said after we exchanged numbers.

When the office finally approved the travel date, about one month before departure, they also added that I’d be travelling with someone else – Chris, from the video team.

We’d barely interacted before the trip. All I knew of him was his first name, where he sat, and the videos he edited.

When we eventually left, it was a Saturday, July 2, six months after I first pitched it. Beyond the things we were making and dispatching back to Lagos, our only link to the office was a WhatsApp group with our support team back at the office.

“What is your mission here?” Mr Smiley hits me with the follow-up.

“We’re journalists,” I explain. “We’ve been travelling around Nigeria for the past twenty-seven days, and this is our current stop.”

He pauses, then asks again, “What is your mission here?”

I repeat my answer. He asks again, and as I begin to answer, I’m a little irritated. “We’re journalists – Jesuloba, Chris, and me. Mansur is our friend here in this town. We’re travelling across Nigeria, and this is our Biu stop.”

Mr Smiley is in mufti, but he’s a soldier, and we’re sitting in the Intelligence Office of the Biu Military Cantonment, Borno State, the front lines of Nigeria’s war against Boko Haram.

“Hmm. Journalists,” he looks at us as if expecting to spot journalism in our eyes.

At the time of leaving Lagos, I’d worked in a newsroom for over two years, but this trip is the first time I identify as a journalist. I’ve covered beats from celebrity reporting to tech and even metro stories. Of course, I’m talking man-kills-neighbour-over-piece of yam metro.

Because I spent most of that time sitting in an office, curating stories, monitoring trends and writing about them, it felt less like journalism and more like regular content creation. Something to make a person stop scrolling, click, and read. But on this trip, I’ve worn journalism like a badge, but mainly as a shield. Like when a truckload of police officers crossed us in Benin, we could either be cultists or journalists. Or, when we reached checkpoints in border towns, we could either be illegal immigrants or journalists. I’ve called myself a journalist so much on this trip that I’ve started to feel like one.

He asks again. At this point, I’m not sure if it’s the fourth time or the umpteenth, but I outline our itinerary.

A month earlier, we left Lagos from Oshodi on a Sunday at dawn while one megaphone threatened Hell to everyone in weaves. Another was calling people for morning prayers, and a third was telling women squeezing through the parked buses not to break the side mirrors with their breasts.

Our first stop was Ijebu Ode, where we went to the tomb of a dead queen, which living women aren’t allowed to enter – only men. Then Idanre Hills, where we climbed 682 steps and instead of Heaven, we found the remnants of an ancient people who lived on the hills for 800 years but descended a century ago because of colonialism.

When we reached Benin, our first stop was the Oba’s palace, where even though we couldn’t see the king, we got to hang out with the virgin boys who dedicate their lives to the service of their kingdom. Waiting for us outside the palace was Jesuloba, carrying a backpack and holding a camera – it’s where his trip with us began.

In Asaba, we met a septuagenarian who escaped the Asaba massacre of ‘67 but still suffers survivor’s guilt. Onitsha is where we saw the new Nollywood – it’s also where we saw the first glimpses of Nnamdi Kanu’s Biafra.

We didn’t meet Kanu himself until five stops later, where he was living a walking distance from the Governor of Abia State and surrounded by believers. When Kanu stepped out of his house, a woman in crutches burst into tears at the sight of him. She’d come from Asaba. Another man brought a ram as a gift and asked him to bless it. Finally, at six pm, the Biafran flag in the compound, the only flag, was lowered to mark the end of the day.

Our next stops were Calabar, Uyo, down to the rice marshes in Ebonyi, then up the old coal mines in Enugu. Next was Makurdi, then Jalingo, and up we went to one of Nigeria’s highest towns, Gembu. When we descended, we were off to Jimeta-Yola, and after Yola, we began to see what a country at war looked like. In Mubi, we found entire sections of buildings chewed away and blackened by Boko Haram’s firepower. On our road to Maiduguri, we passed Chibok and the school that brought Boko Haram global infamy.

“So, why did you choose to come to Biu?” Mr Smiley cuts in before I can reach the part about how we got to Biu from Maiduguri.

“Instagram,” I say, trying to remember the specific message amidst the hundreds I’d received in the past month. “You can even follow everywhere we’ve passed through from Instagram.”

“What?”

Let’s start from the day before we came to Biu.

Thursday, August 3, 2017.

We’re at the park, waiting for a bus headed for Potiskum in Yobe State when someone sends a DM on Instagram.

“If you’re still in Borno, you should go to Biu. Our people are so brave; Boko Haram has never conquered them.” It had my attention.

The sender is Nafisah. I have no idea who she is. But I also did not know who Sugar in Abakaliki was, Abubakar in Kakari, or Ebuka in Oguta. So paranoia didn’t bring us this far.

“Chris, I think we should go to Biu,” I say.

Chris thinks it’s a bad idea. “But it’s not on our itinerary na,” he says. Chris’ first instinct has always been to say no to anything that puts our safety to question. He had concerns about visiting a dissident’s home and problems with getting help from strangers everywhere. Chris is a reasonable man, but we didn’t end up here by saying no.

“Gembu wasn’t on our itinerary,” I say, “but we went there, and we didn’t regret it.” A biker we met in Port Harcourt said, “if you must go around the country, then make sure you go to Gembu.” So we went. Gembu was breathtaking for the scenery with greenery for as far as the eyes can see, and its below-fifteen-degree temperatures.

The biker is Inyang, who once rode across every border state in Nigeria in one stretch. Another time, he rode from Lagos to Austria in less than 40 days – he ferried his bike into Spain at a port in Morocco.

Chris is throwing reasons why we shouldn’t go; I’m countering with reasons why we should until I suggest that we leave it to chance.

“I asked her if she can give us someone’s phone number there,” I say, “if she doesn’t send it in 20 minutes, we’ll go to Potiskum.”

The number came in 12 minutes. It’s her uncle’s, and he’s a member of the Civilian Joint Task Force, CJTF, a coalition of civilians – hunters, vigilantes, and people tired of sitting around, waiting for providence to save them from Boko Haram.

The road to Biu is cratered and treacherous, but the military checkpoints are the main event. First, you have to step out of the vehicle, then walkthrough with your hands up, while the driver has to step out and push his car through.

My old friend Musa, in whose Teaching Hospital dorm we stayed while we were in Maiduguri, told me about his first time at one of these checkpoints.

“I was walking through a checkpoint just outside Maiduguri when someone called me. As I dropped my hand to grab the phone, two soldiers screamed and almost opened fire.”

Phones are an ingenious way to trigger bombs remotely, and the sight of one at a checkpoint always triggers soldiers.

We reach Biu about five hours later, but it’s not her uncle waiting for us; it’s her baby brother, Mansur. He’s tall, dark, and it’s not hard to tell he’s a teenager. His uncle joins us minutes later – he’s small and frail, and for a moment, you forget that this man has taken up the duty to hunt down Boko Haram fighters.

He shows us to a hotel just on the outskirts of town, opposite a military checkpoint, and tells us that by morning when he returns; he’ll be taking us to the leader of the CJTF in Biu.

“Tomorrow is going to be lit,” I tell Chris and Jesuloba. Chris just nods.

Our good morning at Biu on Friday is at the makeshift office of the CJTF – it’s an old school with two blocks that haven’t seen a student since the holidays began, but that’s not our first stop. First, we need permission to speak to the CJTF from the Local Government chairman, whose office is right beside the school, looking equally dilapidated.

“He’s not at the office,” Mansur’s uncle says, “let’s go to his house.” It’s only a few minutes from the office, and when we reach there, there’s a man supervising people pouring sand and gravel on the eroded part of his residence.

He’s displeased that we’ve walked from his office to his house at past ten in the morning. So he yells at us to wait for him at his office or the CJTF office until he’s ready to work. It’s ten in the morning.

We head back to the CJTF office. About a dozen men are sitting in the room. They look like regular people – traders, or farmers, or vigilantes. Everyone in this room is here because they signed up to protect their people from Boko Haram. At any cost.

Sometime in 2014, the CJTF patrolled this town with impaled heads of dozens of Boko Haram fighters. When you’re in a room like this, you keep an unassuming face while thinking, who did the killing, who did the beheading? Which of these hands impaled those heads?

The only way I learn who the leader is is the one everyone is looking at to speak.

We’re about to get into the introductions when another man steps in. He’s no less than 6”2, with a scruffy beard covering his sunken cheeks.

“Why are you people here,” he says, half-yelling.

“We –”

“This is not how to do things!”

“But tha –”

“You cannor just come here and just be going anywhere you like. Who are you? Come outside!”

Everyone in the room starts heading out as he storms out, many of their faces confused, so we follow. Outside, there’s a white Hilux. A guy in the front seat is trying to record on a tab secretly. His lack of discretion is so tacky that I flash a smile and wave at his camera.

I don’t know when I stop hearing what Mr Six Plus is saying, but the yelling is getting irritating. I know men like him – the one who isn’t in charge but feels the need to assert himself over the group and its actual leader.

Mansur’s uncle tries to pacify him while the leader of the group watches silently. Finally, Six Plus’ yelling ends with, “let’s go to the barracks.”

When we reach the Intelligence office, and Mr Smiley tells him he can leave, I’m relieved to no longer be sharing a space with him again.

“Why didn’t you take permission before coming to Biu?” Mr Quiet, the man, sitting at the back, asks.

“As I said earlier,” I begin to explain, “this entire road trip is about learning what it means to be Nigerian in Nigeria today. So, for example, we didn’t realise we had to take permission before coming to this town, or any Nigerian town for that matter.”

“Have you taken any photos since you came here?” Mr Smiley asks.

“No, we haven’t; we haven’t even had time to go anywhere. Mansur’s uncle has followed us everywhere.”

Mr Smiley is not convinced.

“I need you to understand that you’re not under arrest,” Mr Smiley says, “we just need to confirm that you’re who you say you are, not a spy for another country or a Boko Haram.”

A spy? Flattering.

“What’s in your bag?” Mr Smiley asks. In less than 5 minutes, the table in front of him has all our gear and phones. A lady steps into the office when Mr Smiley calls her and starts checking through all the photos on our memory stick, looking for traces of Biu or whatever else she’s looking for.

Mr Smiley is looking through my phone. There are at least 500 photos there taken from the past month alone.

“Are these not Ogbunike Caves?” he asks.

“Ah, yes.”

“That’s in...Anambra State. It’s less than 100 kilometres from Onitsha,” he adds.

We do this Geography Trivia as he looks through all the photos, mapping out over a dozen landmarks and places. The man knows his geography by kilometre.

“I need you to understand that you’re not under arrest,” Mr Smiley says again. More light is flooding the room through the left window as the sun begins its descent.

It’s past four.

When they’ve looked through all the photos to their satisfaction, he tells me the whys—something about security and intel, and how the people of Biu must be safe.

“I need to make a video,” Mr Smiley says as he whips out his phone, “did we harm you or torture you?”

I laugh nervously, “no, you didn’t.”

“Did we take any of your belongings?”

“No.”

“That is all. You can grab your things,” Mr Smiley says, and his smile is patronising. We’re leaving when Mr Quiet says he also has to take a photo.

All four of us line up in a straight file, mugshot style, in front of a wall outside.

“Are you still staying at Biu or –”

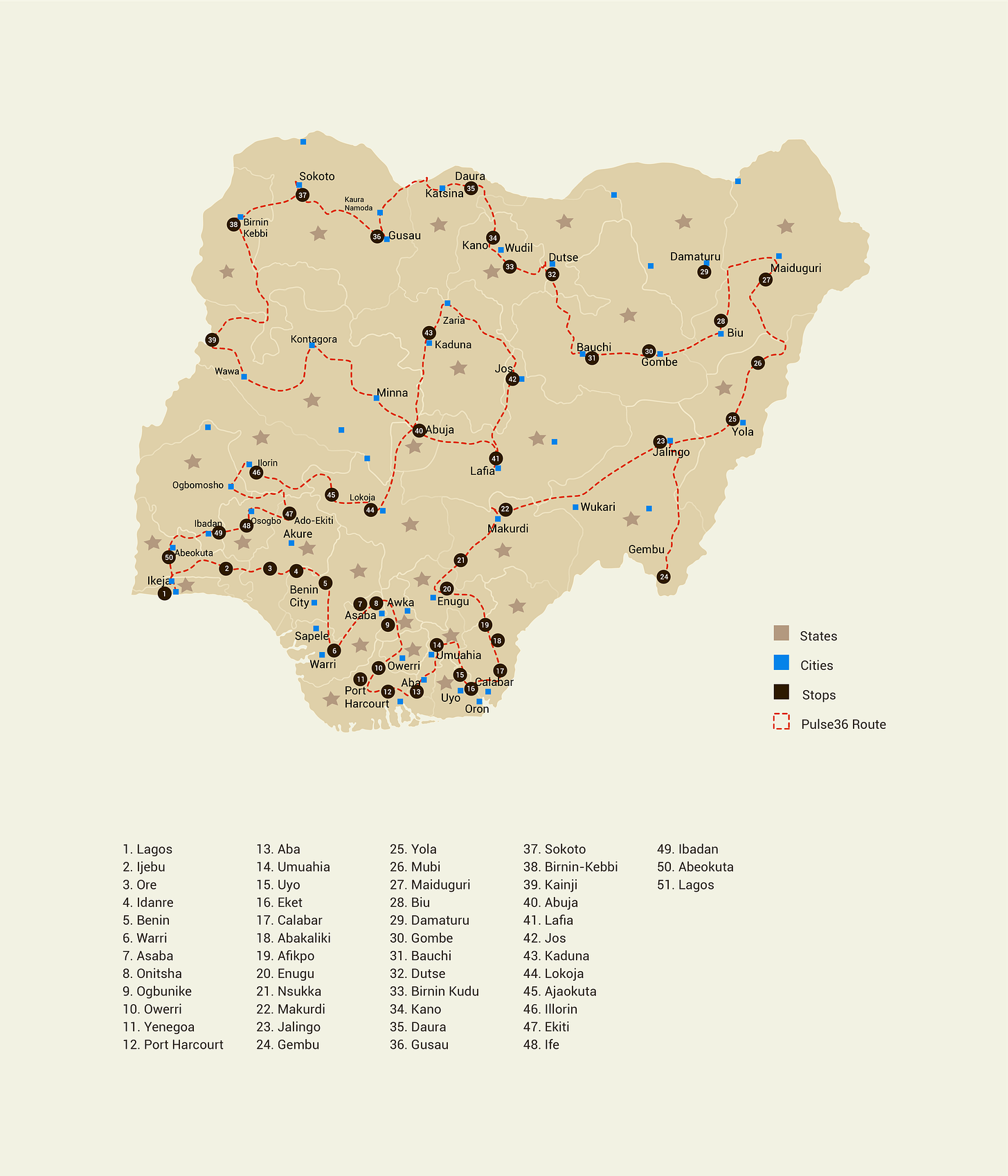

“No, thank you,” ‘Loba, Chris and I say together. “We’re going to Gombe.”

“Let me drop you off at the park,” Mr Quiet offers, but it’s not a suggestion. “Mansur can go home from there.”

The last cab for Gombe leaves at a few minutes past six. Chris and I squeeze into the car’s front seat – I’m seated between him and the driver. Jesuloba is at the back with three other people. Google Maps say we’ll be there cramped up like sardines for only three hours.

The first time I open my eyes from sleep, it’s dark. Chris is sleeping too. The driver’s eyes, like our headlights, are piercing into the darkness. Jesuloba is sleeping, but one of the other three people at the back are awake.

The second time I wake up, we’re at a military checkpoint—the driver parks on the side of the road. The next few moments happen fast. The first assault comes from the torchlights in my eyes and Chris’.

“Come out!”

But they don’t even wait for us to come out before they drag Chris and me out.

“Sit down there!” One of them orders.

“Oya, stretch your leg!” Another one says.

At a military checkpoint, I’m sitting on the ground at night, exhausted, half-awake, confused, on a highway between Biu and Gombe. It’s a wrong place to be when you haven’t had a good haircut, your beard is scruffy, and your name is Fu’ad. I’m thinking about how my mum used to call me Muhammadul Fu’ad, and I hate that thought so much.

I’m almost dizzy with the sound of my own pounding heart. I look up to see Chris is wearing his tracksuit. He has a gold chain on his neck. It’s night, but I know Jesuloba’s tattoo is still on his neck. Oh, Christopher. Oh, Jesuloba, Jesus is King. The Christianity in their names and the Igbo in Chris’ blood comforts me.

They order us off the roadside and to the front of a building, walking in a single file. More soldiers are standing in the dark, over us. One of them is looking at his phone and then back at us, one face at a time. I’m thinking about my name and about how I just heard one of the officers say something that sounded like Yoruba.

“Barracks la ti n bo,” I say, a little desperate to identify, by any means necessary, that I am, in fact, a Fu’ad from a faraway place.

Two soldiers shut me up simultaneously – a third shut up is a dirty slap on my right cheek from behind. I’ve had a long life of many slaps, so it didn’t hurt, but in that brief moment, that dark highway in the middle of nowhere is bright as day.

“Where’s the fourth person?”

They know who we are; they know the vehicle we left Biu in – it takes a few seconds before I realise what’s happening. It’s Mr Quiet’s photo and free ride – after all, he didn’t leave the park until after we’d moved. I feel betrayed.

“The person that sent you the photo from Biu forgot to mention that the fourth person is actually from Biu, so he’s not travelling with us. We’re from the Barracks, and that’s what I was trying to say earlier.”

My tone is slap worthy going by the last one, but I don’t care.

The officer whose phone everyone has gathered around and the most senior looks at me, quiet. Finally, he tells us to get up before pulling me to the side.

“I’m sorry for what that soldier did,” he says, “sometimes, our men can get overzealous. I need you to understand that you’re not under arrest; we’re just waiting for further instructions from Biu.”

He introduces himself as a lieutenant; I introduce myself as a journalist.

He walks away for a few moments while I rejoin Chris and Jesuloba. I bring them up to speed about nothing.

The lieutenant returns a few minutes later.

“The C.O. wants you back at Biu,” he says. “We have to leave now. Do you want to collect your change from the driver?”

When I get to the driver, he’s too scared to say anything, so he just stutters. Being the driver of a vehicle carrying potential Boko Haram members is bad for his life expectancy. I tell the lieutenant not to worry about my change.

“Let’s go.”

I fall right asleep as the back of my head touches the headrest in the Hilux. When I wake up, we’re at another checkpoint, and this time, we’re getting handed over to another Hilux.

“They’ll take you back to Biu,” the lieutenant tells me.

Chris, Jesuloba and I squeeze into the back; our escort is another lieutenant who’s riding shotgun.

He introduces himself and tells us we do not need to worry.

“I hope you don’t mind,” he says as he plugs in his aux cable. It’s Wizkid philosophising about Ojuelegba on the road to Biu. I fall asleep again.

When I wake up, it’s to walk into the Officer’s Mess. We’re tired and hungry. The bar is closed. A TV is on, and a soldier is talking to the press about how they have forty days to capture Shekau, dead or alive.

I rest my head on a couch at the bar, and when I open my eyes again, it’s morning.

Saturday, August 5, 2017.

The first person I see that isn’t Chris or Jesuloba is the lieutenant from last night. He has one of those faces that look familiar, like he’s a friend from a time past. The part of the barracks where we’re at is so quiet it almost feels empty.

“Hope you slept well,” he asks, or something like that. I’m hungover from stress, but I try to make small talk.

“You know, there’s a version of things where I could have been in your uniform too,” as we get talking.

“Eh ehn, how?”

“That time when we were in secondary,” I start explaining, “Nigerian Navy Secondary School – we wanted to go to ND –”

“Ojo or Abeokuta?”

“Abeokuta,” I say.

“Ahh, I went to Nigerian Navy Primary School.”

I throw some names at him; old classmates I know serving are in the army. I ask about one of them; “ah, he’s with the Special Ops.” I ask about another, “ah, na 54th Artillery hin dey.” I throw out a few more names, some stick, and others don’t.

“I have a friend too, serving here in Borno,” Chris says, “he told me that he’s mostly at checkpoints.”

Eventually, we get to the “why are we still here” part. It’s not hard to tell that he knows something he’s not allowed to say to us, but he reassures us. Then, finally, he leaves, but when he returns less than an hour later, we know it’s time to move.

“I hope you’ve packed,” the lieutenant asks. But, of course, we didn’t even unpack.

We walk to the nearest road within the barracks, and I see the doorway first, then the wall. The building on the other side of the road is where we were held for six hours the day before.

“Good morning,” an officer says, walking towards us, but it looks like he’s marching. Everyone around him is at attention, so it’s not hard to tell that he’s the Commanding Officer.

“Who’s the leader of this team,” he asks.

I raise my hand. When I drop it, it’s for a handshake. His grip is firm, but his face is reassuring; he’s a Colonel.

“We’re going to Damaturu, and you’ll ride with me in this vehicle,” he says to me, and before I can even respond, he says, “the rest of your team will go in the other vehicle.”

I see the Hilux from the night before in its true camo colours. Inside it, there’s one officer riding shotgun; the other one is behind the wheels.

The Colonel is already tucked into his seat by the time I get around the truck to sit behind the driver.

Between us is an armrest. On the floor between our feet is a bulletproof vest and a helmet held up by a rifle.

As we’re driving out, I see the one person I wasn’t expecting to see – Mansur.

“My superiors have asked that we bring you for questioning,” the Colonel begins to explain, “it’s nothing serious. Everyone just likes to double-check here.”

“Damaturu? That’s Yobe State.”

“Yes, yes,” he says, “I need you to understand that you’re not under arrest; they’re just trying to be thorough.”

I’ve heard that before.

We’re driving out of Biu now, a convoy of two. What was only an open road the last time we passed, it was different this time.

There’s a large crowd everywhere in front, large enough that the two trucks have to stop – on the roadside, on the main road. It’s also a thunderous crowd, and as we go closer, it appears that the crowd is shouting in unison. They can’t be less than a thousand or maybe even three. Some of them are on foot. Others are hanging from the back of jalopies — men and women of all ages.

“You read what people say about the army and the work we do,” the Colonel says, “and you’re sad.”

The crowd is chanting one word.

“But when you see the people, the people you’re fighting for,” the Colonel sighs before he continues, “everything becomes worth it.”

“Dole! Dole! Dole!” the crowd chants.

Biu people are a farming people, and every farm day, the Colonel explains, soldiers in collaboration with the CJTF escort people to their farms, protect them all day, then return with them.

“Dole! Dole! Dole!”

A few minutes later, we make our way past the crowd and begin on our way to Damaturu. Every time we pass a small settlement, people would run out to wave. Fathers with their kids on their shoulders. Shouting dole. Dole means force, but its popular use is in the official name of the counter-terrorism operation by the armed forces, Lafiya Dole; Peace By Force.

In between, the Colonel and I are in conversation, hopping from topic to topic. We talk about everywhere we’ve been for work. We talk about the relationship between the media and the military.

“You media people just write all kinds of things,” he says.

“That’s because the military refuses to speak to the media,” I explain, “and what happens is that people take the little information they have and try to piece it together.”

“But some of the information might be sensitive,” the Colonel says.

“The media won’t know what is sensitive or not if you’re not even talking to them at all.”

He talks about herders and how we have the most herdsmen related insecurity, even when we don’t have the most cattle in Africa. Ethiopia does. He talks about how he doesn’t believe that open grazing is a thing that should still be happening.

We talk about the NYSC, and he talks about how he prefers the Egyptian system of National Service – conscription into the military. Not strange, coming from a man on the front lines who understands the importance of reserves.

I lose track of how long we’ve been moving or all the things we’ve talked about, but eventually, we reach a checkpoint and park beside the highway we’ve been travelling on. There’s a checkpoint there, and it’s low growth on either side of the road. A few houses adorn the landscape.

He meets another soldier halfway – the soldier is also with a two-truck convoy. When the Colonel returns, it’s to say his goodbyes.

“I have to hand you and your team over to these people,” he says, “this is where my jurisdiction ends, and I have to return to Biu. They’ll take you to Damaturu.” We’re at the boundary between Yobe and Borno State.

When I see Chris and Jesuloba, it’s like we haven’t seen each other in years. Mansur looks hearty, but I suspect he might be scared.

“Why did they tell you to join us na?” I ask.

“It’s that man from yesterday,” he’s talking about Mr Quiet. “He came to the house this morning and told my mum that I’m going to come back today. He promised.”

“I’m so sorry, man.”

“No problem, sir.”

Chris is talking to one of the soldiers when his face goes cold. The soldier tells Chris in Igbo, “forget all these guns you’re seeing; you see this road we’re about to pass? Just pray.”

This time, I’m sitting in the back seat of my truck alone. The leader of this party is riding shotgun in the Hilux I’m in. He turns around, looks at me and says, “do not step out of this vehicle under any circumstance.”

“Oya,” he says to the pilot, who starts driving.

We haven’t driven for up to thirty minutes when we reach a small town – it’s scanty with buildings, left and right. When I was a child, I believed towns like this only existed along the highway, with no life behind them.

To our left, a sign reads something-something Buni-Yadi. This place sounds familiar.

“This is the school that Boko Haram attacked in 2014,” the soldier in front of me says to me. In February 2014, Boko Haram visited the Federal Government College while the students slept.

A dorm room in a Federal Government college will have bunks line each side of the rooms, close to the windows. The windows are designed for cross ventilation; they’re also great if you’re Boko Haram and need to inflict terror. It started with the grenades getting thrown into the rooms from the windows. Then came the indiscriminate gunfire towards the windows, picking out boys trying to jump out. The students who didn’t meet bullets met knives, slitting their throats.

When morning came, the count said fifty-nine boys didn’t make it through the night.

Not too long after we pass Buni Yadi, our trucks come to a sharp halt. We’re about 50 metres from what is stopping us – cows crossing in their dozens. Soldiers sitting in the back of the Hilux jump down and flank each side of our truck, arms at a ready and crouching.

It’s quiet, so fucking quiet.

“E be like na Oga cows,” and I see the soldiers ease up and hop onto the back of the trucks again.

“See these cows,” the leader explains, “sometimes Boko Haram push them onto the road and use them in an ambush.”

There’s no way any Hilux runs over cows with bones that will crush fenders and knock engines.

Our driver enters gently when we reach potholes, like a toddler trying to make it down the stairs. When you drive into potholes, you curse the government. But here, you enter potholes with your heart in your mouth and come out of them with gratitude because “Boko Haram puts IEDs inside the potholes, and it can just go gbao.”

A lot of the potholes are, in fact, bomb craters.

We reach another point where we start hearing gunfire ahead of us. To my right is a vast savannah. There’s no sign of enemy life as far as my eyes can see. I look at my chances and know I have none, so it’s me and the truck, no matter the circumstance.

A few minutes later, we learn it’s soldiers on a drill.

“Ah, e go be this new Captain make their morale dey high.”

They’re talking about a new officer who’s been transferred to the unit with the gunfire. The soldier, it appears, gets moved around to new units where morale is low so that he can fire the fighters up.

It should have been a two and a half hour trip to Damaturu from Biu, but we eventually reach our destination after almost four hours.

The trucks finally come to a halt at the Divisional Headquarters of the war against Boko Haram. The last thing I hear before heading into the office where someone wants us is a soldier talking about his child back home.

The first office I’m called into is not an office – it’s something else. The walls are covered with maps like wallpaper. I’m fighting the urge to trace places out on them, but I’m also trying not to send the wrong signal. Two men are sitting behind a table. Just before I settle into a chair in front of them, I spot a CCTV in the corner of the room.

“So, why are you here?”

From top to bottom, I do the whole narration again, how we left Lagos, and how we ended up here. About how I didn’t think we needed permission to travel across Nigeria. When I step out of the room, they ask me to call Chris. When Chris comes out, Mansur goes in, then Jesuloba. Everyone gets the same questions.

Then, we wait. We sit around and wait at the shed meant for packing. The empty spot is a makeshift mussalla for the Muslim soldiers. It’s also where we’re asked to wait. Jesuloba pulls out a cigarette for his nerves. Chris and I pull out our phones for Whatsapp.

Chris sends updates to the Whatsapp group about what the soldiers are up to this time. We’ve been sending updates daily to a Whatsapp group with people back at the office – Osagie, my Editor in Chief; Ani, Chris’ boss, and Head of Video; Tunde, the head of this travel Project: Pulse36.

As Chris is texting, I’m also texting my friends, and everyone is asking one thing: what the hell is happening?

“We’re fine,” I say in the Whatsapp group.

“No, we’re not fine o,” Chris says, “these people are still holding us.”

One of our interrogators has come out for a smoke break, and he’s telling us that we’re good to go, and they’ll soon sign our release papers. Jesuloba supplies a lighter.

Release papers, and we aren’t under arrest. Right.

Our interrogator is telling us about what life is like on the frontlines. About how he’s interrogated over 100 Boko Haram suspects, and many of them can’t recite Fatiha, an essential prayer in Muslim canon.

From him, I hear for the first time that Boko Haram is, in fact, in factions: the Shekau faction and the Al-Barnawi faction. Al-Barnawi is the son of Boko Haram’s founder, Mohammed Yusuf.

“If you go now,” our interrogator says, “Shekau can give you ten million naira cash inside Sambisa.”

He talks about how they have a sense of where Shekau is but can’t reach him because of the human casualties. It’s not just the Chibok girls in harm’s way; it’s thousands of other people kidnapped at different points since their campaign of terror began.

One other soldier joins us for a smoke. He’s itching to speak, and when he opens his mouth, his superior, our interrogator, shuts him up.

“What’s happening,” my friend texts on Whatsapp.

“We’re waiting for them to bring our release papers,” I say.

My friend wants to tweet about our predicament, and I’m saying it’s not that serious. Twitter, I believe, can over-escalate things. Ha.

“They have their usefulness. Imagine if you were really detained. The tweets would create enough attention; they’d have to release you.”

To everyone on Whatsapp, the only thing more stressful than being held is how unbothered I am. Panic is hopeless and torturous, so I just sit and try to talk.

“Can I use your phone to call my mum,” Mansur asks me and a few moments later, he’s talking to her over the phone, telling her not to worry.

“They’ll soon allow us to go,” he says to her.

Not long after Mansur’s call, one of our interrogators tells us that our release papers are now ready and will need to be signed at another office. All four of us squeeze into the backseat of the truck; a military policeman is riding shotgun. There’s not enough room at the back, so I have to lap the helmet and bulletproof vest.

The first thing I notice about our next stop when we get there a few minutes later is the fence – it’s abnormally high. The security guard at the entrance is in a black polo shirt, brandishing a rifle, but it’s not a conventional rifle we’ve seen anywhere in the past few days.

“That gun looks like an Israeli issue,” I whisper to Jesuloba.

“Ehn?” he leans in to hear what I’m saying, but so does the military policeman in the front seat.

“Nothing.”

I know the rifle; I just can’t remember where I’ve seen it.

The military policeman steps out to speak to the security. While we’re waiting in the backseat, I’m looking at the helmet and vest on my lap and having war correspondent fantasies. A few days ago, Jesuloba saw a soldier on the treacherous Damboa Road. A handwritten inscription at the back of his helmet reads, “KILL THEM ALL. CHECK BACK.” I wonder what I’d write on my helmet to make it truly mine.

I place the vest on my chest and wear the helmet, then I take a picture, just to see what it looks like.

I’m beaming when the gates swing open, and our driver goes in.

“I’m coming; let me go to the office,” the policeman says, paper in hand before he walks away.

“You people are journalists ehn,” the driver asks.

“Yes,” then we go on to tell him how we ended up here.

It’s his turn to talk now.

Sometimes,” he begins, “I see what soldiers are going through whenever I go inside the bush, and I cry.” They spend days, even weeks, living there. Cooking there. Arguing about football. Fighting and dying, losing morale or gaining ground.

He talks about Abuja – not the capital city 100 kilometres from where we are – but the one outside Damaturu. This Abuja is a ditch.

“We go just carry those Boko Haram,” he explains, “tell them say we dey carry them go Abuja. And once we reach the Abuja like this, you go just use one leg push them inside the hole, use bullet follow them – pa-pa! pa-pa!”

He’s about to start talking about family life when the military policeman returns, this time with another man in the black polo shirt, holding the type of rifle we saw earlier. They ask us to come along with them to the building, with our bags too.

I remember the gun now. It’s a Tavor – TAR51—Israeli-made assault rifle. I remember where I’ve seen it in the past. In Owerri, Imo State, right outside a building. The building had a small security post like the one we’ve just seen too.

At the reception, a man is waiting. He can’t be less than 6”4, and when he walks, he does so as if the ground is trembling under his feet.

The 6”4 man looks at us, and I can’t tell whether he’s tired or irritated, but he says, “off your cap, off your belt, off your shoes. Drop your bag here.”

I look up, and there it is. There’s a picture of President Buhari and another of the Yobe State Governor. The third photo has a man whose designation says that he’s the Head of the DSS in Yobe State.

Tavors are mostly used by officers of the Department of State Security (DSS).

I laugh, but it’s a laugh of utter defeat. We’ve been interrogated twice, snatched from a car in the middle of nowhere, transported across states, and now, we’re about to be detained. I am crushed.

The time is now past six in the evening, and as I’m handing in my phone, Mansur’s mum calls. Six Foot Plus takes the phone from my hand gently, squeezes the button on the side till the call ends, and the phone goes off. Then, he instructs me to write down everything I’ve submitted at the counter.

“Go there,” Six Foot Plus points to a room opposite the reception. Inside it, there are two windows to the left, with two single-seater couches. To the right, there’s a longer couch. At the far left of the room is a door that leads to a small toilet.

My legs can’t hold, so I sit down. Chris is taking off his belt. He’s wearing the same jacket he was wearing at the park in Maiduguri – the same day we were choosing between Biu and Potiskum. He’s asked to take that off too. He’s walking towards me when Six Foot calls him back and tells him to take off his chain and wrap it in a piece of paper.

Chris is right. Biu is a wrong turn. I let him down. I let Jesuloba down. Now, I’ve pulled Mansur into this, separated him from his mum, and now she’ll be growing sick with worry.

“I’m sorry, Chris,” I say to him as he walks into the room and takes a seat beside me. He pauses for a moment, bites his nails before he says, “it’s fine.”

I apologise to Jesuloba and Mansur as they come in too.

Six Foot Plus steps into the room, takes a peek at the toilet as if to check if it still works and begins to walk out again, not saying a word.

“Are you going to leave us here,” Jesuloba protests. All of us are sitting on the edge of our seats now.

Six Foot Plus pauses at the entrance, looks slowly at Jesuloba and says, “do you want to sleep in the cell?”

Everyone leans back into the chair. No one says a word after, but I’m the first to fall asleep.

When I wake up, it’s another man at the door, and he’s instructing us to get up and follow him. I’m holding my jeans with one hand to prevent them from falling, and as we walk past the reception, the clock says the time is past ten.

We enter a large, empty room. It looks like it should be an office, but there are no chairs nor tables. He throws in some pillows and tells us that’s where we’ll be sleeping for the night.

Everyone just throws their pillows on the ground, buries their cheeks in them, and fall right back to sleep.

Sunday, August 6, 2017

It’s hard to tell what time it is, the clock at the reception is not within view. We have no watches. The thing about being held against your will is that the enemy is time. You have so much of it but so little to do with it. You try patience, but what is patience when you have no precise way of measuring the passing of time?

We start our day back in the room with the couches. Everyone is restless, pacing. The man from the night before who showed us our sleeping places returns again. This time, it’s with toothpaste and toothbrushes.

We tell him we don’t need brushes, “we need answers.”

He shows up later with a giant tray with plates of food. It's the answers we want, not food. But this man, this caretaker, he’s calm every time.

When the waiting starts to eat you up, your brain spits out funny thoughts. Chris is the first to speak.

“What if they take us to Abuja?”

“Well, then when we get there, we’ll –” it’s mid-sentence that I realise that he’s talking about Abuja the ditch.

“They can’t try it,” I say, and for a moment, I’m wondering what’d have happened if my friend had, infact, gone on Twitter for insurance.

Mansur speaks next. It’s about his mum and how he’s worried about her blood pressure. There’s not much I can say to soothe a boy who’s scared about losing his mother, but I can distract him. I can distract all of us.

“Have you decided what you want to study in Uni,” I ask Mansur a few moments later when everyone has gone quiet again.

“Computer Science,” he says. But, then, he talks about his school choices. He could go to Lagos to be with his father and sisters or to the newly commissioned Military-run university in Biu.

It’s the conflict between wanting to see a bigger world in Lagos or staying home in the furthest town.

I give a small speech, throw in some advice, so do Chris and ‘Loba. We share stories about school life, ideas and extracurricular activities.

Silence.

I start talking about love. Mansur has a crush on an old classmate. We tease a little, then silence again.

“What if they tell us to cancel this road trip,” Chris asks.

“They’d have to tie me down, so I don’t leave Lagos again,” I’m livid at the thought of it, “but the moment they ship us to Lagos, I’m taking the next vehicle to Gombe and continuing.”

Silence. The Caretaker comes to check that we’ve eaten – he sees that we haven’t touched it. He leaves with the tray in hand without saying a word.

I suggest a game or two. We play Concentration. We play riddles. We crack jokes and laugh. Silence.

The sun outside looks scorching from the single window in the room, but there are no shadows – it has to be noon.

It’s also around this time another man comes to our holding room.

“You’re the people they brought from Biu,” I can’t tell if he’s asking or stating a fact he already knows. We respond to the affirmative, just as he’s settling into the chair closest to the door.

“I’m not happy,” he says, “I’m not happy at all o!”

Everyone is confused.

“Why haven’t you eaten? Food is your fundamental human right!”

We’re more confused, but one thing we’re sure of is that he’s the most superior person we’ve spoken to since we stepped into this building. He’s wearing glasses, has very little hair on his head, and looks like he’s in his early sixties.

He reminds me of an old uncle; I just don’t know which one.

“I want you to know that there’s no problem,” he says, “it’s just the process, and everyone is just checking on their end.” He tells us he’ll be seeing us in a few minutes.

The next person we see a few minutes later is not Grand Uncle; it’s Six Foot Plus.

“Oya, follow me,” he says and walks off, his potbelly leading the way. The next room we enter looks like a classroom. There’s a large board, tables and benches for sitting.

Grand Uncle is seated in front, and another man is beside him. He’s wearing a Bama cap and looks like he doesn’t talk much.

They make us sit at different ends of the room, hand us sheets of A4 and pens, and tell us to write everything about how we ended up here.

I don’t know how long we write for, but we finish around the same time. We sit in our chairs quietly as grand uncle skims through the pages. Then he starts his speech. It’s nothing we haven’t heard about the way Nigeria is today about taking permission. About how nowhere is safe.

I try not to interrupt, though I have a lot of things to say.

“Even the Biu that you say has never been attacked,” that’s not what I said, “it has been attacked, and people died!”

Just after dawn on January 14, 2015, Boko Haram fired their first shots in Biu. A few hours of intense fighting later, the insurgents were repelled, a few killed, and five captured alive. Things quickly returned to normal as shops reopened.

“But I need you to know that – ”

“We’re not under arrest,” I finish it for him.

When we return to our room, a fresh tray is waiting. It’s the first meal we’ve had in about 24 hours.

A few hours later, we’re sober again. I’ve heard it before that food will lead to my inevitable demise, and this is all the proof I need. No one has spoken to us since we ate.

When Bama Cap finally shows up, it’s to tell us that our release papers are getting filed but that we’d inevitably be spending one more night.

The rule of thumb with Nigerian detention: if you get held on a Friday, there’s no way you’re getting out until Monday.

Monday, August 7, 2017

The first papers arrive for signing in the morning with Mr Bama Caps. It’s the standard info; personal details, occupation, and the likes.

As he collects our papers together, I catch a glimpse of the stack he’s adding them to. I notice a name, or half of it: Abdul-something-something. Occupation: Boko Haram Fighter.

It’s the first time since all of this began that I properly consider how close we’ve been to things going completely south – I just didn’t care much before. I’m thinking now about the CJTF office and how things might have turned out. South at the barracks. South at the checkpoint. South on the way here. South, right here.

I wonder who’s in the cell and how long they’ve spent there. DSS cells, I’ve heard, are the absence of light and hope.

“We’ve invited a surety to sign off on your release papers,” Bama Cap says.

Our surety, when he eventually shows up, is a Yobe-based journalist with a National newspaper. Even he is a little nervous. He doesn’t know us personally and understands that if we are anything they might have at some point suspected us of being, he’s in trouble too. But he takes the chance, signs for us, and makes all the difference.

“I can’t believe you’ll do this for us,” Chris tells our Surety, “You don’t even know us, but you’re helping us.” I’m thinking about the conflict Chris is having and what it means for him to navigate life with paranoia.

The evening is arriving, and so are the senior officers of the DSS – they’re primarily dressed in kaftans and donning Bama caps. Our bags have resurfaced, and we have to check everything we’ve logged in to make sure all our belongings are complete.

“I can’t find my chain,” Chris says a few moments later.

“Did you leave it here? Are you sure?” one of the officers asks.

“Yes!”

“Then why is it not here?” another one asks.

“I dunno, but I kept it here.” Chris is already angry.

“Nobody is leaving here until we find that chain,” one officer says. “Nobody has ever come here and lost anything.”

I saw his chain. I saw him wrap it in a small piece of paper and drop it on the counter, where Six Foot Plus instructed. It could have ended up in the trash because someone thought the paper belonged there or could have ended up with someone. I don’t know, but I walk up to Chris.

“Chris, are you sure?” I ask as I place my hands on his shoulders.

“Yes now!”

“Are you sure that maybe it didn’t fall on that highway on Friday night?” I asked again.

“Guy, I’m su –”

“Try to remember,” I ask again, squeezing his shoulder even tighter, “maybe it’s not here.”

He pauses, and looks at me.

“It’s not here,” he says. His shoulder loosens, and his head falls in resignation. A necklace is not going to be the reason we spend another night here.

The state head of the DSS secures a hotel for us, and it’s where we spend the night. It’s an offer we can’t refuse, not because it’s too good, but because gestures like this aren’t a choice.

Tuesday, August 7, 2017.

We reach the park before most people in Damaturu reach their places of work. We want to be in the first car leaving Damaturu. Mansur will be on his way home to his mum, who’ll most likely be waiting by her door till he’s in her arms.

For the time she couldn’t reach her son, her mouth didn’t touch any food. Everyone has heard stories of boys and young men picked up by security forces and never returning home because they were suspected of being Boko Haram. Whether or not they were found guilty in a court of law didn’t always matter, there’s a ditch named Abuja, and they must feed it.

By pure luck, we run into one of the soldiers we’d encountered on Saturday – he’s the one his superior won’t allow speaking to us during the smoke break.

I know he has stories when he says, “the things wey my eye done see,” so we prod him for a few while we wait for the car we’re going in to fill up with passengers.

He’s Igbo, lives in Lagos when he’s not on the frontlines, and loves his girlfriend deeply. “She love me, but her love no reach make she follow me come this place,” he says.

He drinks beer with one of Lagos’ infamous gangsters when he’s on leave, but his life on the frontlines is even more thrilling.

He’s a bomb disarmer, he says, and he’s “disarmed so many bombs that they use at the training school in Makurdi, that they’ve stopped collecting new bombs.” So instead, they just make them destroy the bombs.

There’s a scar on the inner part of his arm, and he got it once while they were out on assignment. There was a bomb, and his team had been dispatched to disarm it. Just while he was getting into it, Boko Haram came out guns blazing, it’s an ambush, and when they shot him to kill, the bullet grazed his upper arm.

He has more stories, but our car is now ready to go.

“Thank you, chairman,” I say. We pay for his bus without him asking and head out.

I don’t know how long I’ve been sleeping but when I wake up, it’s because we’re at a police checkpoint. The policeman is wearing a black t-shirt and slippers. Another officer is at a corner, sitting down. It’s the first checkpoint I’ve seen anyone sitting by the road since we entered the northeast.

I roll my eyes before I catch myself. A policeman is a sign that whatever is in front of us is better than whatever it is we’ve left behind. It’s the first time we’ve seen a policeman in over a week, and for the first time, the sight of a police checkpoint brings with it a sigh of relief.

Thank you:

- SI, Ope, Mariam and Afolabi for the edits. Ruka for the strong-armed editing, and Jyte for hounding me for three years to write an anthology – manage this one like that.

- Thank you, Chris, Jesuloba (and Koko) for the trip of a lifetime.

Beast of a report man. You clearly have no word count limits. Looking forward to reading more of these.

I really enjoyed reading this. As others have said, it was like I was with you - so lucidly written. Somehow, I am happy-sad. Happy to get a glimpse into NE Nigeria but sad that this is what MY country has become. Abba, please intervene. Thank You.